Understanding Curriculum - Single page view

Understanding Curriculum

Understanding Curriculum

Curriculum is the essence of any education system. Education is the transfer of knowledge, attitudes and skills from one generation to the next generation but the curriculum “reflects (the) forms of knowledge, habits of thinking, and cultural practices that a society considers important enough to pass on to succeeding generations” (Triche, 2002, p. 1). Therefore, knowing about curriculum is essential for teachers. This guide will help you in understanding the concept of curriculum.

References

Achilles, C. M., Finn, J. D., Prout, J., & Bobbit, G. C. (2001). Small classes big possibilities. The School Administrator, 54(9), 6-15.

Allington, R. L. (2002). You Can't Learn Much from Books You Can't Read. Educational Leadership, 60(3), 16-19. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/495/

Bhatti, A. J. (2015). Curriculum audit: Analysis of curriculum alignment at secondary level in Punjab (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). International Islamic University Islamabad, Pakistan.

Berliner, D. C. (1984). The half-full glass: A review of research on teaching. In P. L. Hosford (Ed.), Using what we know about teaching. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Bobbit, F. (1918). The curriculum. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Bruner, J. S. (1960). The process of education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Caswell, H. L. & Campbell, D. S. (1935). Curriculum development. New York: American Book Company

Cornbleth, C. (1990). Curriculum in context. New York: Falmer.

Danielson, C. (2002). Enhancing student achievement: A framework for school improvement.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Doll, R. C. (1996). Curriculum improvement: Decision making and process, (9th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Eisner, E. W., Vallance, E. (1974). Five conceptions of curriculum: Their roots and implications for curriculum planning. In E. W. E. E. Vallance (Ed.), Conflicting Conceptions of Curriculum (pp. 1-18). Berkley, PA: McCutchan Publishing.

Ellis, A. K. (2004). Exemplars of curriculum theory. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education. Farber, S., & Finn, J. (2000). The effect of small classes on student engagement. Paper presented at annual AREA meeting in New Orleans, LA.

Giroux, H. A., Penna, A. N. & Pinar, W. (1981).Curriculum & instruction : alternatives in education . Berkeley, Calif.: McCutchan Pub. Corp.

Glatthron, A. A., Boschee, F. & Whitehead, B. M. (2006). Curriculum leadership: Development and implementation. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Good, C. V. (Ed.). (1988). Dictionary of education, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. Goodson, I. F. (2010). Curriculum reform and curriculum theory, in J. Arthur & I. Davies (Eds.) The Routledge education studies reader. London: Routledge.

Gordon, C. W. (1957). The social system in the High School. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Hopkins, L. T. (1941). Interaction: The democratic process. Boston: D. C. Heath.

Johnson, M. Jr. (1967). Definitions and models in curriculum theory. Educational theory 17 (2).

McNeil, J. D. (2006). Contemporary curriculum in thought and action (6th Ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Nussbaum, M. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Psifidou, I. (2007). International trends and implementation challenges in secondary education curriculum policy: the case of Bulgaria (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain.

Rugg, H. O. (1927). Curriculum making: Past and present. In C. Davis (1927). Our evolving high school curriculum. Yonkers-on –Hudson, New York: World Book.

Saylor, J. G., Alexander, W. M. &Lewis, A. J. (1981). Curriculum planning for better teaching and learning, (4th ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Tanner, D. &Tanner, L. (1995). Curriculum development: Theory into practice, (3rd ed.). New York: Merrill.

Triche, S. S. (2002). Reconceiving curriculum: An historical approach (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Louisiana. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/nov02/vol60/num03/You-Can%27t-Learn-Much-from-Books-You-Can%27t-Read.aspx

Turner, J. R. (2003). Ensuring what is tested is taught: Curriculum coherence and alignment. Arlington, VA: Educational Research Service.

Tyler, R. W. (1957). Curriculum then and now. In Proceedings of 1956 Invitational conference on testing problems. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Wolk, S. (2010). What should students read? Phi Delta Kappan, 91(7), 8–16.

Definitions of Curriculum

The term curriculum has been defined in so many ways that it has become a hard to pin down term (Psifidou, 2007 p. 17). Different philosophies of education, divergent learning theories, and different approaches and theories of curriculum have contributed to the establishment of assorted definitions of curriculum. However, this variety in definitions of curriculum does not indicate its ambiguity but its comprehensiveness and richness of its scope. Actually, each definition communicates a particular aspect or characteristic of curriculum adding its depth and breadth. Some educationists think that curriculum is confined to content as it is “a systematic group of courses or sequences of subjects” (Good, 1988, p. 157), others consider it to consist of “the formal and informal content and process by which learners gain knowledge and understanding, develop skills, and alter attitudes, appreciations, and values under the auspices of school” (Doll, 1996, p. 15). Some think it to be an “output of the ‘curriculum development system’ and an input to the ‘instructional system’” (Johnson, 1967, p. 130), some others consider it to be a “plan for providing sets of learning opportunities for persons to be educated” (Saylor, Alexander & Lewis, 1981, p. 8), and some others suggest that curriculum includes the “entire range of experiences, both directed and undirected, concerned with unfolding the abilities of the individual” (Bobbit, 1918, p. 43) or “all experiences children have under the guidance of teachers” (Caswell & Campbell, 1935, p. 66).

Ellis (2004, pp. 4-5) has grouped these definitions into two categories developed further below:

1. Prescriptive definitions

2. Descriptive definitions

Prescriptive definitions

Some definitions are prescriptive because these define curriculum as “how things ought to be” in the schools. These definitions acknowledge the dominant role of the institution or teacher who is influencing the learners. Here, the institution or teacher is responsible for transforming the learners’ personality in such a way that it is accepted by the society. Educationists like Dewey, Rugg, Tylor, and Triche give a prescriptive definition of curriculum: when they suggest that

- Curriculum is revamping of child’s experience to “the organized body of truth” (Dewey, 1902, p. 11)

-

Curriculum prepares learners for “meeting and controlling life situations” (Rugg, 1927, p. 8)

• Curriculum is sum of “all the learning experiences planned and directed by the school” (Tyler, 1957, p. 79)

• Curriculum is purposeful and embodies “a society’s past, present and future beliefs” (Triche, 2002, p. 1).

Descriptive definitions

Some definitions are descriptive because these define curriculum as “how things are” in the schools. In these definitions, educationists put the learners in focus and define things happening with respect to the learners. Some definitions of this category are given below.

- Curriculum includes everything which the learner willingly receives and assimilates so that it shapes his future behaviour (Hopkins, 1941)

- Curriculum is the “interaction” of students with the teacher, knowledge and environment (Cornbleth, 1990).

- Curriculum causes a change in the learner’s knowledge and experience that helps the learner in managing situations around him wisely (Tanner & Tanner, 1995, p. 189).

Types of Curriculum

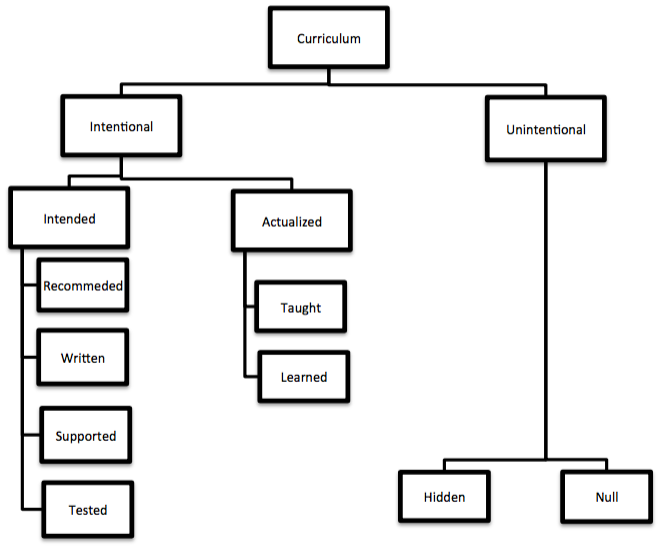

The diversity in curriculum definition also continues to exist in describing its types. Different writers have used different terminology and categories of curriculum. However, it is interesting that many curriculum specialists have used different terminology for the same type of curriculum. Figure1 gives an outline of different types of curriculum.

Figure 1: Types of curriculum

Recommended Curriculum (also known as Ideological Curriculum)

The Recommended Curriculum is the name given to the curriculum construed by the educational stakeholders at the national level. It is more general and usually consists of policy guidelines. It actually reflects the impact of “opinion shapers” such as:

- policy makers

- educationists

- scholars

- professional associations

- legislators.

The Recommended Curriculum provides a basic framework for the curriculum. It identifies the key learning areas. It specifies the boundaries as well as the destination. So, it guides the curriculum coordinator in formulating the academic standards to be achieved through various teaching-learning programmes. National educational policy is a form of Recommended Curriculum.

Written Curriculum (also known as Enacted curriculum or Curriculum)

The Written Curriculum is the curriculum that is sanctioned and approved for classroom delivery. It represents society’s needs and interests. It translates the broad goals of the “Recommended Curriculum” into specific learning outcomes. Glatthron, Boschee, and Whitehead (2006, p. 9) note that the “Written Curriculum” is specific as well as comprehensive and it indicates:

- Rationale of curriculum

- General goals to be realized

- Specific objectives to be achieved

- The sequence of objectives

- Kinds of learning activities

The Written Curriculum is authentic where it is product of visionary educators and where it has deep and life-lasting effect on the learners (Wolk, 2010). The Written Curriculum can be (a) generic or (b) specific to region. The generic “Recommended Curriculum” is usually developed at national level and is used at variety of educational settings. On the other hand, region specific curriculaare developed for a particular site usually district.

The Written Curriculum is a practicable plan as it is result of compromise between the ideals recommended by the experts and the real situations suggested by the teachers, pupils and parents. Therefore, it is essential that teachers must have a clear understanding of the Written Curriculum to interpret the demands of curriculum as enacted in government documents. Moreover, the professional development of teachers must be aligned with the Written Curriculum.

Supported Curriculum

The Supported Curriculum is the curriculum supported by available resources. Such resources include both human (teachers) as well as physical (such as textbooks, workbooks, audio visual aids, teacher guides, grounds, buildings, library books and laboratory equipment). The Supported Curriculum not only plays a vital role in developing, implementing, and evaluating the curriculum, it also affects the quantity and nature of the learnt content (Glatthron, Boschee, & Whitehead, 2006, pp. 10-14).

Research indicates that teacher-student ratio (e.g. Achilles, Finn, Prout, & Bobbit, 2001; Danielson, 2002; Farber & Finn, 2000), the allocation of amount of time for a particular subject, and the quality of the textbooks (Allington, 2002) play a key role in students’ learning. These are all elements of Supported Curriculum.

Taught Curriculum (also known as Operational Curriculum):

The curriculum that is delivered by the teachers to the students is termed as Taught Curriculum. Teachers, being the chief implementers of curriculum, occupy a crucial role in curriculum decision making. Taking the students into consideration, they decide how to achieve the intended learning outcomes. They decide the distribution of time to a particular activity/content. Even the external pressures like external exams cannot limit their freedom to exercise their own philosophy of instruction. In some countries teachers are given considerable authority regarding curriculum, instruction and choice of instructional resources, in others these choices are limited.

Learned Curriculum (also known as Experienced Curriculum)

All the changes occurred in the learners due to their school experience are called the Learned Curriculum. It is the curriculum that a learner absorbs or makes sense of as a result of interaction with the teacher, class-fellows or the institution. It includes the knowledge, attitudes and skills acquired by the student. Many educationists have defined curriculum as everything the learner experiences. This emphasizes the dominance of the learner in the curriculum and excludes all that which has no effect on the learner. Thus, only the learned curriculum becomes the curriculum.

Assessed Curriculum (also known as Tested Curriculum)

The curriculum that is reflected by the assessment or evaluation of the learners is called the Assessed Curriculum. It includes both formative and summative evaluation of learners conducted by teachers, schools, or external organizations. It involves all the tests (teacher- made, district or standardized) in all formats (such as portfolio, performance, production, demonstration, etc.). The assessed curriculum is significant as it enables the stakeholders to evaluate the impact of Written and Taught curricula upon the learners. It determines the level of the Learned Curriculum. Research (e.g. Berliner, 1984; Turner, 2003) indicates that the mismatch between Assessed and Taught Curricula has serious consequences.

Hidden Curriculum

Gordon (1957) was first to identify that a part of the Learned Curriculum was due to unintended results of activities or efforts of the institutions. This is called the hidden curriculum. It is unintentional because the teachers as well as other members of the educational institution convey messages that are not part of the officially approved curriculum. For example, the behaviour and attitude of the teachers may affect the students. Moreover, it may also be the unintentional consequence of some act. An example of Hidden Curriculum occurs when a student (dis)likes some teacher’s teaching strategy and consequently begins (dis)liking the subject taught by that teacher. Both positive and negative messages are included in the hidden curriculum. McNeil (2006, p.193) admits that Hidden Curriculum is “part of school ethos” and controls much of the students’ learning, behaviour and social conduct.

Null Curriculum (also known as Excluded Curriculum)

The Null Curriculum is that which is not taught. Sometimes the teacher ignores some content or skill, deliberately or unknowingly. A teacher may consider some idea unimportant and ignore it. Similarly, teacher may avoid detailed description of some topic for the one or other reason, for example, evolution in Biology. Sometimes also, the learner fails to learn certain knowledge, skills or attitude for various reasons.

Curriculum Conceptions

Several theoretical frameworks have been proposed for designing or adapting curriculum. Curriculum experts like Eisner and Vallance (1974) and Giroux, Penna, and Pinar (1981) have critically analysed these different conceptions of curriculum. McNeil (2006) categorized different conceptions of curriculum in to following four groups:

- Humanistic Curriculum

- Social Reconstructionist Curriculum

- Systemic Curriculum

- Academic Curriculum

Humanistic Curriculum

The learner as human being has prime significance for the Humanistic Curriculum which aims at development and realization of complete human personality of the student. The humanistic curriculum does not take student as subservient to society, history or philosophy but as a complete entity. The humanistic curriculum experts suggest that if education succeeds in development of needs, interests, and aptitudes of every individual, the students will willingly and intelligently cooperate with one another for common good. This will ensure a free and universal society with shared interests rather than conflicting ones. Thus humanists stress on individual freedom and democratic rights to form global community based on “common humanity of all people”.

The Humanistic Curriculum is based on the belief that the education that is good for a person is also best for the well being of the nation. Here, the individual learner is not regarded as a passive or at least easily managed recipient of input. S/he is the choosing or self-selecting organism. To design the Humanistic Curriculum, we have to focus on the question “What does the curriculum mean to the learner?” Self-understanding, self-actualization, and fostering the emotional and physical well being as well as well as the intellectual skills necessary for independent judgment become the immediate concern of the Humanistic Curriculum. To the humanists, the goals of education are related to the ideals of personal growth, integrity, and autonomy. Healthier attitudes towards self, peers, and learning are among their expectations. The concept of confluent curriculum and curriculum for consciousness are the important types of humanistic curriculum. Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Locke, Rousseaue, Kant, and Pestalozzi are some of the great humanists of the world history.

Social Reconstructionist Curriculum

Social Reconstructionists are dissatisfied with the social, political and economic order of society and take curriculum as vehicle for reconstruction of the society. They advocate a curriculum which gives vision of an ideal society and ensures “reconstruction” of present society on the basis of that vision. The Reconstructionists suggest that curriculum should confront the learners with issues which mankind face and this curriculum should develop in learners the ability of critically analysing these issues and finding out the possible solutions. Consequently, the learners will develop deep understanding of the society and they will strive for better social order. Social adaptation and social reconstruction approaches are very important here. The social adaptation approach refers to awareness of students about the social problems and giving the students solutions of these problems. On the other hand, social reconstruction refers to developing in students critical awareness of social problems and seeking changes in basic structure of society to improve the real world. The Social Reconstructionists may be grouped into following categories:

1. Freire’s social reconstructionism (Revolution)

2. Neo-Marxists (Critical inquiry)

3. Futurolgists

For further reading please see: Schiro, M. S. (2013). Curriculum Theory Conflicting Visions and Enduring Concerns (2nd ed). SAGE Publications, Inc (pp.151-198).

Systemic Curriculum

The Systemic Curriculum reflects a coherent systemic strategy for each level of the education system beginning from expectations to achievement. The important features of Systemic Curriculum or standard-based curriculum are:

1. Setting standards and learning outcomes for the students

2. Complete alignment among policies, curricular framework, instructional materials, classroom instruction and assessment

3. Reorganization of the whole education system for maximizing students’ achievement with respect to already specified learning outcomes

4. Evaluation of students’ achievements, identification of deficiencies and accountability of the concerned.

The basic concept behind systemic curriculum is having objectives, adopting measures to achieve these objectives, and assessing continually to see if all the elements are working harmoniously for achieving the specified objectives. The systemic curriculum is said to serve as egalitarian interests as it focuses on measures of equal access for all. It also facilitates in accountability of all the concerned educational stake-holders as it sets predetermined standards and efficiency of stake holders can be measured with respect to these standards. Here teacher tries to adhere to the already specified objectives or standards.

For further reading please see: Margaret E. Goertz, M. E., Floden, R. E., & O’Day, J. (1995). Studies of Education Reform: Systemic Reform, Volume I: Findings and Conclusions. Link https://www2.ed.gov/PDFDocs/volume1.pdf

Academic Curriculum

The advocates of Academic Curriculum believe that every academic discipline has a particular structure and curriculum should develop in students understanding of basic principles of that structure. By adopting that structure, the students would go more deeply into the knowledge, create more ideas, and validate their ideas. The learning gained through this process would also enable the learners to make use of acquired knowledge in other contexts.

Bruner (1960) suggests that there may be following three kinds of structures in any discipline:

- Organizational structure

- Substantive structure

- Syntactical structure

The basic idea behind academic curriculum is to facilitate students in learning “how to learn?”. This curriculum tries to induce in students the methodology and procedure adopted by the specialists to discover new knowledge. This is done by introducing students to intellectually challenging situations to enable them understand and adopt the basic structure of the particular discipline.

1. Societal level

At the societal level, curriculum is developed by the federal level agencies, boards of education, publishers, and curriculum reform committees. The curriculum developed at this level is mostly based on theoretical knowledge and is mostly reflection of the educational policy rather than field experience. However, school administrators, teachers, parents, and students are also usually consulted to make it more practical. It is prescriptive and general, giving less space for individuality or local needs. Here, the politicians, corporate leaders and organizations are more influential in shaping the curriculum. However, the curriculum is then developed by the professional experts such as curriculum specialists, subject specialists and psychologists. It serves the egalitarian interests and brings uniformity throughout the country. For achieving the advantages of this type of curriculum, efforts are required for maximum alignment at state, district, school, and classroom level.

2. Institutional Level

Here, the curriculum is developed by the school administration and teachers. However, the students, parents as well as the local community may also be involved. Curriculum at the institutional level is more aligned to the institutional goals. The vocational and training schools often develop their own curriculum according to the nature of particular job or skill they are going to prepare students.

3. Instructional Level

The instructional level curriculum is developed by the classroom teacher. The teacher sets the learning outcomes keeping in view his actual experience of the learners. It is based on practical knowledge of the learners and the locality. However, it may lack the depth and breadth. The effective teachers develop the curriculum that is also aligned to national policy and standards.

4. Personal Level

Here, the learners are not passive recipient of knowledge them but they are choosing and self- managing learners. They construct their own meanings from their classroom experiences. This curriculum is challenging, but flexible, innovative and learner-friendly. It allows the learners to grasp clearly the learning goals and progress purposefully through active learning.

Nussbaum’s (2000) concept of ‘practical reason’ and ‘affiliation’ is much important here. ‘Practical’ reason implies that the learners must reflect critically upon the plan of their life and formulate their personal goals. ‘Affiliation’ means having ability to live effectively with others and showing exemplary social interactions. This is possible when the learners are empowered to make decisions about themselves. The Magnet Schools in America (which offer diverse options to the students in choices of individualized curriculum) are examples of institutions where personal curriculum decisions are made. The Montessori approach which supports discovery learning and self-directed learning provides another example.

Strength of Evidence

Areas for further research

If you are researching in this area, please let us know so that we can add this information to the guide. An important linked area is the aims of education. The findings reported in Bhatti’s theses indicate the importance of ensuring that the aims of education are aligned with the curriculum (all aspects) and the assessment experience of students. If a wholistic view is not taken by curriculum planners then the desired outcomes are not likely to be achieved.