Autism and Deafness - single page view

Autism and Deafness: Guide

|

|

Autism and Deafness

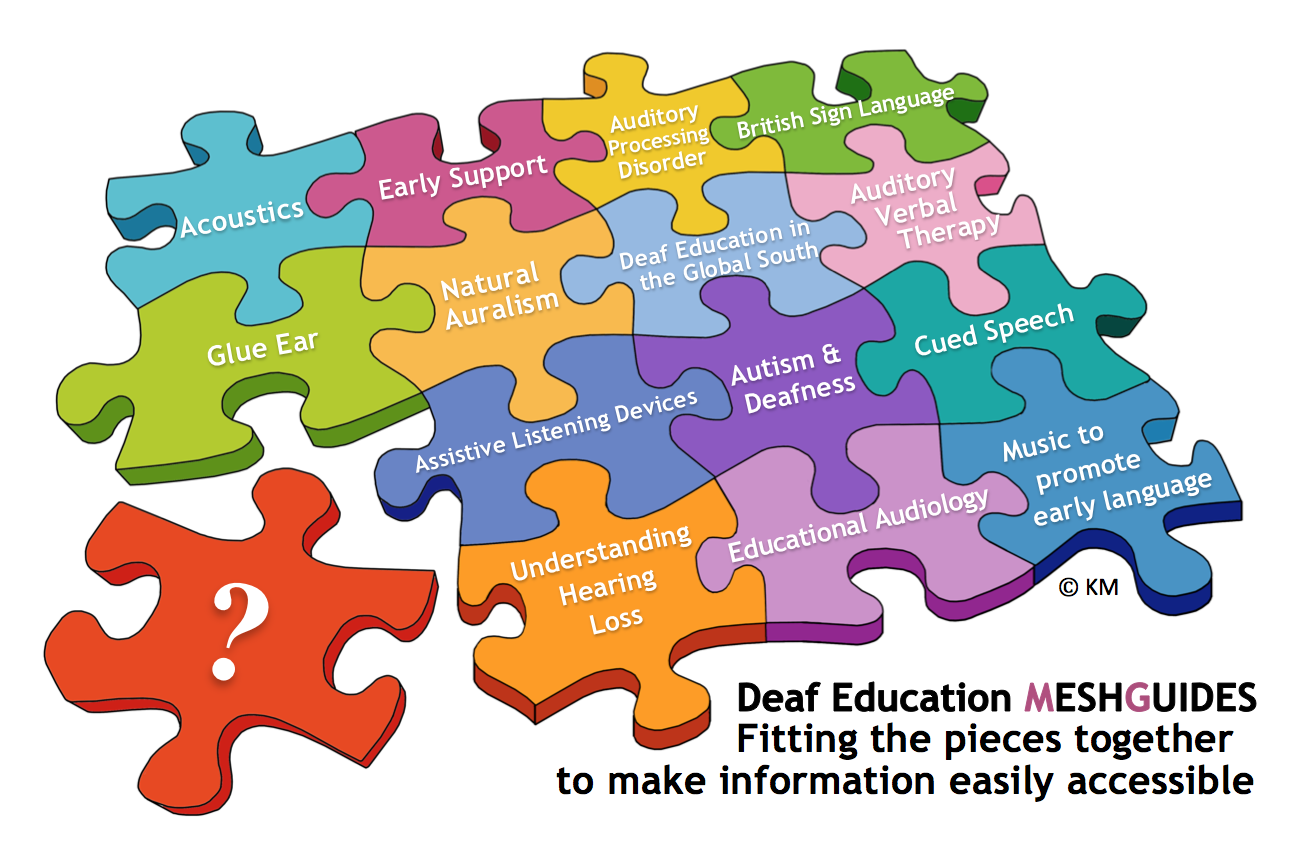

This MESHGuide is for all those looking for, and needing, information on children and young people with a diagnosis of Autism and deafness. Currently (2022), the limited information that exists is spread across many platforms. This MESHGuide collects together, in one place, a range of informative documents and useful links for professionals and families.

Christina Borders (1DEI 2016) suggests that two language-impacting disabilities increase the need for strong evidenced-based practices but goes on to report 'a dearth of available resources and direction for teachers and professionals supporting comorbid deafness and ASD'. It is hoped that the limited research and evidence based practice currently available and included in this MESHGuide will result in the triggering of further research into this important area.

The population of students with complex needs has doubled since 2004 (2Anne Pinney 2017). This includes ‘children with complex forms of Autism [who] have more than doubled since 2004, to 57,615.’ Early diagnosis of deafness and Autism remains a challenge because both present in similar ways. Teachers working with these students are not able to turn to a breadth of existing practice - this MESHGuide could help. In turn their experience could add to the body of evidence based practice.

Given the small cohort and the individuality of each child/young person the way forward might be through Single Case Design (SCD) research (Wendel et al 2015).

Wendel, E, Cawthon Stephanie W, Jin Jin Ge, Beretas Natasha S. Alignment of Single-Case Design Research with individuals who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing with the what works clearinghouse standards for SCD Research Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2015, 103-114 permissions email: journals.permissions@oup.com

By raising awareness, as the numbers of students increase, the authors hope to identify further reports and research to extend the information available. They invite those of you working with deaf students on the autistic spectrum to use this MESHGuide, report back your experiences and add your own strategies which have effectively supported the learning and social development of your students.

1 Borders et al (2016) A review of educational practices for deaf/hard of hearing students with comorbid Autism; Deafness and Education International 2016 vol 18 no 4 p189-205)

2 Anne Pinney 2017 Understanding the needs of disabled children with complex needs or life-limiting conditions Council for disabled children Report

This guide is one in a series of Deaf Education MESHGuides.

Deafness Articles

References on ‘deafness’ which may link with indicators of autism

Dye, M.W.G, Hauser, P.C. Sustained attention, selective attention and cognitive control in deaf and hearing children (2014) Hearing Research, 309, pp. 94-102.

James, D.M., Wadnerkar-Kamble, M.B., Lam-Cassettari, C. Video feedback intervention: A case series in the context of childhood hearing impairment (2013) International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 48 (6), pp. 666-678.

Lee, Y., Jeong, S.-W., Kim, L.-S. AAC intervention using a VOCA for deaf children with multiple disabilities who received cochlear implantation (2013) International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 77 (12), pp. 2008-2013.

Leeds, C.A., Jensvold, M.L. The communicative functions of five signing chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) (2013) Pragmatics and Cognition, 21 (1), pp. 224-247.

Marshall, C.R. Word production errors in children with developmental language impairments (2014) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369 (1634), art. no. 20120389, . Cited 2 times.

Morgan, G., Meristo, M., Mann, W., Hjelmquist, E., Surian, L., Siegal, M. Mental state language and quality of conversational experience in deaf and hearing children (2014) Cognitive Development, 29 (1), pp. 41-49.

Snodgrass, M.R., Stoner, J.B., Angell, M.E. Teaching conceptually referenced core vocabulary for initial augmentative and alternative communication (2013) Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29 (4), pp. 322-333.

Wellman, H.M., Peterson, C.C. Deafness, thought bubbles, and theory-of-mind development (2013) Developmental Psychology, 49 (12), pp. 2357-2367.

Autism Articles

Articles on autism

Allman, M. J., & DeLeon, I. G. (2009). “No Time Like the Present”: Time Perception in Autism. In Giordano, A. C. et al. (Eds.), Causes and Risks for Autism (65 – 76). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Asperger, H. (1991). Autistic Psychopathy in Childhood. In U. Frith (Ed.), Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome (37 - 91). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (Original work published in German in 1944).

Attwood, A. (2003). Understanding and Managing Circumscribed Interests, In M. Prior (Ed.), Learning and Behaviour Problems in Asperger Syndrome (126 – 147). New York: The Guildford Press.

Baron-Cohen, S. & Wheelwright, S. (1999). ‘Obsessions’ in children with Autism or Asperger Syndrome: Content analysis in terms of core domains of cognition. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 484 – 490.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2009). Autism: The Empathizing-Systemizing (E-S) Theory. The Year in Cognitive Neuroscience, 1156, 68 – 80.

Boucher, J. (2001). Lost in a Sea of Time: Time-parsing and Autism. In C. Hoerl & T. McCormack (Eds.), Time and Memory (p. 111 – 135). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berger, E., D’Souza, L & Miko, A. (2021) School-based interventions for childhood trauma and autism spectrum disorder: a narrative review The Educational and Developmental Psychologist Vol. 38, No 2, 186 – 193.

Chen, G. M., et al. (2012) Constructing Autism Frontiers in Psychology (3:12) Oxford/New York

Crozier, S & Sileo, N., M. (2005) Encouraging Positive Behaviour with Social Stories – An Intervention for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, Teaching Exceptional Children, 37, 6, 26 -31.

Grace Megumi Chen et al. (2012) Constructing Autism Frontiers in Psychology(3:12) Oxford/New York

Boucher, J., Pons, F., Lind, S., & Williams, D. (2006) Temporal Cognition in Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders: Tests of Diachronic Thinking. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37:1413 – 1429.

Caldwell-Harris, C.L. & Jordan, C.J. (2014). Systemizing and special interests: Characterizing the continuum from neurotypical to Autism spectrum disorder. Learning and Individual Differences, 29, 98 – 105.

Cascio, C.J., Foss-Feig, J.H., Heacock, J., Schauder, K.B., Loring, W.A., Rogers, B.P., Pryweller, J.R., Newsom, C.R., Cockhren, J., Cao, A., & Bolton, S. (2014). Affective neural response to restricted interests in Autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55:2, 162 – 171.

Courchesne, E., Townsend, J., Akshoomoff, N.A., Saitoh, O., Yeung-Courchesne, R., Lincoln, A.J., James, H.E., Haas, R. H., Schreibman, L., & Lau, L. (1994). Impairment in Shifting Attention in Autistic and Cerebellar Patients. Behavioral Neuroscience, 108, 5, 848 – 865.

DuBois, D., Ameis, S. H., Lai, MC., Casanova, M. F., Desarkar P. (2016) Interoception in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 52 (2016) 104 - 111

Engelhardt, C. R., Mazurek, M. O., & Sohl, K. (2013). Media Use and Sleep Among Boys With Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD, or Typical Development. Pediatrics, 132: 1081 – 1087.

Faccino, L. & Allely, C.S., (2021) Dealing with trauma in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Trauma Informed Care, Treatment and Forensic Implications Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, Vol. 30 (8), p. 1082 – 1092.

Fiene, L. & Brownlow, C. (2015) Investigating interoception and body awareness in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder: Investigating interoception and body awareness. Autism Research 2015-12, Vol. 8 (6), p. 709 - 716

Franey Rogers, M & Smith Myles. B (2001) Using Social Stories and Comic Strip Conversations to Interpret Social Situations for an Adolescent with Asperger Syndrome Intervention in School and Clinic 36, 5, 310-313

Goldstein, G., Johnson, C.R., & Minshew, N.J. (2001). Attentional Processes in Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 4, 433 – 440.

Gray, C A (1995) Teaching children with Autism to ‘read’ social situations. In K. Quill (ed), Teaching Children with Autism: Strategies to enhance communication and socialization. (219 – 241) Albany, NY: Delmar

Gray, C & Garand, J (1993) Social stories: improving responses of students with Autism with accurate social information. Focus on Autistic Behaviour, 8, 1, 1 – 10. Happé, F. &Frith, U. (2006). The Weak Coherence Account: Detail-focused Cognitive Style in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 1, 5 – 25.

Happé, F. &Frith, U. (2006). The Weak Coherence Account: Detail-focused Cognitive Style in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 1, 5 – 25

Hatfield, T.R., Brown, R.F., Giummarra, M. J., Lenggenhager, B. (2019) Autism spectrum disorder and interoception: Abnormalities in global integration? Autism Vol 23 (1) 212 – 222

Hare, D.J., Wood, C., Wastall, S. & Skirrow, P. (2015). Anxiety in Asperger’s Syndrome: Assessment in real time. Autism, 19:5, 542 – 552.

Haruvi-Lamdan, N., Horesh, D., Zohar, S., Kraus, M. & Golan, O. (2020) Autism Spectrum Disorder and Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder: An unexplored co-occurrence of conditions. Autism Vol. 24(4) 884–898

Hughes, C. & Russell, J. (1993). Autistic Children’s Difficulty With Mental Disengagement From An Object: Its Implications for Theories of Autism. Developmental Psychology, 29, 3, 498 – 510.

Iskander, J M & Rosales R (2012) An evaluation of a Social Stories intervention. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 7 (2013) 1 - 8

Jordan, C.J. & Caldwell-Harris, C.L. (2012). Understanding Differences in Neurotypical and Autism Spectrum Special Interests Through Internet Forums. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50:5, 391 – 402.

Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact. Nervous Child, 2, 217 – 250.

Keehn, B., Lincoln, A. J., Muller, R-A. & Townsend, J. (2010). Attentional networks in children and adolescents with Autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51:11,1251 – 1259.

Koegel, R., Kim, S., Koegel, L. & Schwartzman, B. (2013). Improving Socialization for High School Students with ASD by Using Their Preferred Interests. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2121 – 2134.

Kuo, M.H., Orsmond, G. I., Coster, W. J. & Cohn, E. S. (2014). Media use among adolescents with Autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 18 (8) 914 – 923.

Landry, R. & Bryson, S.E. (2004). Impaired disengagement in young children with Autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45:6, 1115 – 1122.

Lanou, A., Hough, L., & Powell, E. (2012). Case Studies on Using Strengths and Interests to Address the Needs of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Intervention in School and Clinic, 47:3, 175 – 182.

MacMullin, J.A., Lunsky, Y., & Weiss, J. A. (2015). Plugged in: Electronics use in youth and young adults with Autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 1 – 10.

Maister, L. & Plaisted-Grant, K. C. (2011). Time Perception and its relationship to memory in Autism Spectrum Conditions. Developmental Science, 14:6, 1311 – 1322.

May, T., Rinehart, N., Wilding, J., & Cornish, K. (2013). The Role of Attention in the Academic Attainment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2147 – 2158.

Mazurek, M. O., Shattuck, P.T., Wagner, M., & Cooper, B.P. (2012). Prevalence and Correlates of Screen-Based Media Use Among Youths with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42: 1757 - 1767.

Mazurek, M. O., & Wenstrup, C. (2013). Television, Video Game and Social Media Use Among Children with ASD and Typically Developing Siblings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1258 – 1271.

McConnell, B. A., & Bryson, S. E. (2005). Visual attention and temperament: Developmental data from the first 6 months of life. Infant Behaviour & Development, 28, 537 – 544.

McDonnell, A. & Milton, D. E. M. (2014). Going with the flow: Reconsidering ‘repetitive behaviour’ through the concept of ‘flow states’. Good Autism Practice: Autism, happiness and wellbeing. Birmingham: BILD Publications.

Mercier, C., Mottron, L. & Belleville, S. (2000). A Psychosocial Study on Restricted Interests in High Functioning Persons with Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Autism, 4, 406 – 425.

Murray, D., Lesser, M. & Lawson W. (2005). Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for Autism. Autism, 9: 2, 139 – 156.

Ozonoff, S. (1995). Executive Function in Autism in E. Schopler and G.B. Mesibov (Eds.) Learning and Cognition in Autism. New York: Plenum Press.

Ozonoff, S., Pennington, B. F., & Rogers, S. J. (1991). Executive function deficits in high-functioning autistic children: relationship to theory of mind. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 32, 1081 – 1106.

Pascualvaca, D.M., Fantie, B.D., Papageorgiou, M., & Mirsky, A.F. (1998). Attentional Capacities in Children with Autism: Is There a General Deficit in Shifting Focus? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28: 6, 467 – 478.

Peterson, J.L., Earl, R.K., Fox, E.A., Ma, R., Haider, G., Pepper, M., Berliner, L., Wallace, A.S., & Bernier, R.A. (2019) Trauma and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Review, Proposed Treatment Adaptations and Future Directions Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma 12: 529 – 547.

Reed, P. & McCarthy, J. (2012). Cross-Modal Attention-Switching is Impaired in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 42, 947 – 953.

Rincover, A., & Ducharme, J.M. (1987). Variables influencing stimulus overselectivity and “tunnel vision” in developmentally delayed children. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 91, 422 – 430.

Schmitz, N., Rubia, K., Daly, E., Smith, A., Williams, S., & Murphy, D.G. (2006). Neural correlates of executive function in autistic spectrum disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 59, 7 – 16.

Shafritz, K. M., Dichter, G. S., Baranek, G. T., & Belger, A. (2008). The neural circuitry mediating shifts in behavioural response and cognitive set in Autism. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 974 – 980.

Shane, H. C., & Albert, P.D. (2008). Electronic Screen Media for Persons with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Results of a Survey. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1499 – 1508.

South, M., Ozonoff, S., & McMahon, W.M. (2005). Repetitive Behaviour Profiles in Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35: 2, 145 – 158.

Sukhodolsky, D.G., Bloch, M.H., Panza, K.E., & Reichow, B. (2013).

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Anxiety in Children with High Functioning Autism: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics, 133:5, e1341 – e1350.

Tantam, D. (1991). Asperger Syndrome in adulthood. In U. Frith (Ed.), Autism and Asperger Syndrome (147 – 183). Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Thorne, A (2005) Using an interactive whiteboard to present social stories to a group of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Good Autism Practice, 6, 2, 2005

Trevarthen, C., & Daniel, S. (2005). Disorganised rhythm and synchrony: Early signs of Autism and Rett Syndrome. Brain and Development. 27, S25 – S34.

Vermeulen, P. (2015). Context Blindness in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Not Using the Forest to See the Trees as Trees. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 30: 3, 182 – 192.

Wallace, G. L., & Happe, F. (2008). Time Perception in Autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2: 447 – 455.

Winter-Messiers, M.A. (2007). From Tarantulas to Toilet Brushes: Understanding the Special Interest Areas of Children and Youth with Asperger Syndrome. Remedial and Special Education, 28:3, 140 – 152.

Autism and Deafness Articles

Beals, K. (2004) Early Intervention in Deafness and Autism: One Family’s Experiences, Reflections and Recommendations. Infants and Young Children 17 (4) 284 – 296.

Borders, C. M. Bock, S.,J. & Probst K.M. (2016) A Review of Educational Practices for Deaf/Hard of Hearing Students with Comorbid Autism Deafness and Education International 18(4) 189 – 205.

McCay,V. & Rhodes, A (2009) Deafness and Autistic Spectrum Disorders. American Annals of the Deaf 154, No1, 2009.

Malandraki, G.A. & Okalidou, A (2007) The Application of PECS in a Deaf Child With Autism: A Case Study Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 22(1) 23 – 32.

Myck-Wayne, J., Robinson, S. & Henson, E. (2011) Serving and Supporting Young Children with a Dual Diagnosis of Hearing Loss and Autism: The Stories of Four Families American Annals of the Deaf 156(4) 379 – 390.

Peterson, C.C. (2002) Drawing Insight from Pictures: The Development of Concepts of False Drawing and False Belief in Children with Deafness, Normal Hearing and Autism. Child Development 73(5) 1442 – 1459.

Peterson, C.C. & Siegal, M (1999) Representing Inner Worlds: Theory of Mind in Autistic Deaf and Normal Hearing Children. Psychological Society 10(2) 126 – 129.

Peterson, C.C., Wellman, H. & Liu, D. (2005) Steps in Theory of Mind Development for Children with Deafness and Autism. Child Development 76(2) 502 – 517.

Peterson, C.C., Wellman, H & Slaughter, V (2012) The Mind Behind the

Message: Advancing Theory-of-Mind Scales for Typically Developing Children, and Those With Deafness, Autism, or Asperger Syndrome. Child Development 83(2) 469 – 485.

Rosenhall, U., Nordin, V., Sandstrom, M., Ahlsén, G & Gillberg C. (1999) Autism and Hearing Loss. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 29(5) 349 – 57.

Szymanski, C.A., Brice, P.J., Lam, K.A. & Hotto, S.A. (2012) Deaf Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 42:2027 – 2037.

Vernon, M. & Rhodes, A. (2009) Deafness and Autistic Spectrum Disorders. American Annals of the Deaf. 154(1) 5 – 14.

Wiley, S., Gustafson, S & Rozniak, J (2013) Needs of Parents of Children Who Are Deaf/Hard of Hearing With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 19(1) 40 - 49

Wright, B., Phillips, H., Le Couteur A., Sweetman J., Hodkinson R., Ralph-Lewis A et al (2020) Modifying and validating the social responsiveness scale, Edition 2, for use with deaf children and young people. PLoS ONE 15 (12): e0243162 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243162

Worsley, J. A., Matson, J.L. & Kowlowski, A.M. (2011) The effects of hearing impairment on symptoms of Autism in toddlers. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. 14 (3): 171 – 176.Austen S. (2015) Deafness and autistic spectrum disorder Network Autism.

Young, A., Ferguson-Coleman, E., Wright, B & Le Couter, A (2019) Parental Conceptualizations of Autism and Deafness in British Deaf Children. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2019, 280 – 288.

Background Reading: Autism

American Psychiatric Association, (2013). Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V). Washington, DC: Author. The latest edition of the diagnostic manual.

Attwood, A. (1998). Asperger’s Syndrome: A Guide for Parents and Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. Excellent, easy to read introduction to Asperger’s or High Functioning Autism for parents and professionals.

Attwood, A,(Ed) (2014) Been There. Done That. Try This! An Aspie’s Guide to Life on Earth. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. Personal guidance on how to cope with the daily stresses of living with Asperger’s Syndrome from a number of individuals on the Autism spectrum, with additional professional analysis and recommendations from Tony Attwood.

Baron-Cohen, S. (2008). Autism and Asperger Syndrome: The facts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. An introduction to Autism for professionals and families.

Bogdashina, O. (2003). Sensory Perceptual Issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome: Different perceptual Experiences, Different Perceptual Worlds. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. This book tries to defines the role of sensory perceptual differences in Autism as identified by autistic individuals themselves. A practical, clear and concise book.

Bogdashina, O. (2005). Communication Issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome: Do we speak the same language? London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. A clearly written book that provides a theoretical foundation for understanding communication and language differences specific to Autism. Includes practical recommendations - suitable for professionals and parents alike.

Bogdashina, O. (2006). Theory of Mind and the Triad of Perspectives on Autism and Asperger Syndrome: A View from the Bridge. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. Inspired by the often uncomfortable interplay between autistic individuals, parents and professionals, Bogdashina uses the concept of Theory of Mind to consider these groups’ different perspectives.

Boucher, J. (2009). The Autistic Spectrum: Characteristics, Causes and Practical Issues. London: Sage. A complete and factual overview of Autism and Asperger’s Syndrome. Used as a core textbook on university courses/modules.

Buron, Kari Dunn. (2012).The Incredible Five Point Scale. Kansas: AAPC. An excellent and practical book for anyone working with children/YP who are struggling to manage their emotions.

Fleming, B., Hurley, E. & the Goth (2015) Choosing Autism Interventions. Hove: Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd. An accessible evidence-based overview of the most commonly interventions for children and adults on the Autism spectrum.

Frith, U. (Ed.) (1991). Autism and Asperger Syndrome. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Includes Uta Frith’s first-ever translation into English of Asperger’s original paper, as well as narrative accounts of the syndrome and its varied presentations.

Grey, C (2010). The New Social Story Book. Arlington: Future Horizons. Social Stories are designed to give relevant information about different social situations, thereby decreasing anxiety. This book offers ready-to-use social stories as well as advice on how to effectively use and apply the stories with young children, teenagers and adults.

Gray, C (1994) Comic Strip Conversations: Illustrated interactions that teach conversation skills to students with Autism and related disorders. Arlington: Future Horizons Inc. This book shows how to write a Comic Strip Conversation. A Comic Strip Conversation uses simple drawings to visually outline a conversation between two or more people and serves to help develop social understanding of that particular social situation. Practical and helpful.

Happé, F. (1996). Autism. London: UCL Press. Used as a core textbook on university courses/modules. An informative, well written and highly readable book which is organised into three levels of explanation - biological, behavioural and cognitive, and which attempts to explain the differences in these three domains.

Hoopmann, K. (2021) All Cats Are On The Autism Spectrum. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. An updated version of the original book All Cats Have Asperger Syndrome, this beautiful photo book takes a sensitive look at autism, drawing from the feline world which will strike a chord with all those familiar with autism.

Hoopmann, K (2013). Inside Asperger’s Looking Out. London: Jessica Kingsley. Following on from her original book All Cats Have Asperger Syndrome, Kathy Hoopmann’s book uses engaging text and full-colour photographs to show how neurotypical people with Asperger’s see and experience the world.

Howley, M & Arnold, E (2005) Revealing the Hidden Social Code: Social Stories for People with Autistic Spectrum Disorders London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. This book offers clear and comprehensive advice for professionals, parents and carers on how to write successful and targeted Social Stories.

Jackson, L. (2002). Freaks, Geeks and Asperger Syndrome: A User Guide to Adolescence. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. An enlightening, honest and witty book which addresses difficult topics such as bullying, friendships, when and how to tell others about having Asperger’s Syndrome, school problems and dating. Written by 13 year old Luke Jackson who has Asperger’s Syndrome - this is an excellent personal account.

Lawson, W. (2001). Understanding and Working with the Spectrum of Autism: An Insider’s View. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. Written based on personal experience, Lawson’s book is an essential introduction to Autism for all professionals working in the field.

Lawson, W. (2011). The Passionate Mind: How People with Autism Learn. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. Lawson examines traditional theories of Autism and reveals their gaps and shortcomings. A new theory of Single Attention and Associated Cognition in Autism (SAACA) is introduced. From this new perspective practical suggestions are made for individuals, families and professionals. An essential and accessible book.

LeGoff, D.B., Gomez de la Cuesta, G, Krauss, G.W. & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014) Lego- Based Therapy: How to Build Social Competence through Lego- Based Clubs for Children with autism and related conditions. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing. A complete guide to setting up and running a Lego club for children on the autism spectrum or related social communication difficulties and anxiety conditions. By providing a joint interest and goal, Lego building can become a medium for social development such as sharing, turn-taking and following social rules.

Mahler, K. (2017) Interoception: The Eighth Sensory System. Kansas: AAPC Publishing One of the most important skills we have is being able to understand signals from our body. How do you know if you are hungry, thirsty, tired etc? Those on the autism spectrum tend to lack these skills – this book offers new ways of teaching these skills to individuals with ASD.

McAlinden, D. M (2017) Downloading Grey Thinking. CreateSpace: Independent Publishing Platform. A book/programme to help develop emotional intelligence, build resilience and enable greater self awareness in individuals with Autism.

Sainsbury, C. (2000). Martian in the Playground: Understanding the schoolchild with Asperger’s Syndrome. London: Sage Publications Ltd. This book explores what it means to have Asperger’s Syndrome by providing a window into a unique world. Drawing on her own school experiences and that of a network of friends and correspondents who share her way of thinking, Sainsbury reminds us of the potential for harm which education holds for those who do not fit. Essential reading for all teachers.

Sher, B (2009) Early Intervention Games. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. A resource of fun games for parents and teachers to help children learn social and motor skills. The games are designed to help children feel comfortable in social situations and teach other lessons such as beginning and end, spatial relationships, hand-eye coordination and more. Written by an Occupational Therapist.

Sherratt, D (2005) How to Support and Teach Children on the Autism Spectrum. Cambridge: LDA. An excellent starting point for a teacher or teaching assistant who has has a child in their class with no prior experience. Clear and concise information delivered in an easy to read way.

Silberman, S (2015). Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter About People Who Think Differently. London: Allen & Unwin ℅ Atlantic Books. A book about Autism but also a journey through the history of cognitive difference and our attitudes towards it. Highly recommended.

Smith Myles, B, Trautman, M. L, & Schelvan, R. L. (2004) The Hidden Curriculum: Practical solutions for Understanding Unstated Rules in Social Situations. Kansas: Autism Asperger Publishing Co. A book which offers practical suggestions and advice for how to teach and learn those subtle messages that most people can pick up on almost automatically but that have to be taught directly to individuals with Autism.

Vermeulen, P. (2012). Autism as Context Blindness. Kansas: AAPC Publishing. A groundbreaking book, based on the ideas of Uta Frith. Vermeulen explains in everyday terms how the Autistic brain functions with a particular emphasis on an apparent lack of sensitivity to and awareness of context. Full of examples, often humourous, the book examines ‘context’ as it relates to observation, social interaction, communication and knowledge. This book is a must for anyone working or living with someone on the Autism spectrum.

Whitaker, P (2001) Challenging behaviour and Autism: making sense – making progress. A guide to preventing and managing challenging behaviour for parents and children. London: The National Autistic Society. This book is for teachers and parents of children with Autism. Clearly written, it offers practical strategies for preventing or managing the commonest sorts of challenging behaviour.

Wing, L. (1996). The Autistic Spectrum. London: Constable & Robinson Ltd. An authoritative and compassionate guide to Autism written by world renowned Lorna Wing. This is a sensitive and thorough introduction to understanding and living with Autism. Highly recommended.

World Health Organisation (1992). ICD-10 : Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World Health Organisation. Geneva: WHO. The latest edition of the diagnostic manual

Autism - definitions

Understanding Autism - definitions and associated conditions

Autism is a lifelong, developmental disability that affects how a person communicates with, and relates to, other people, and how they experience the world around them.

Autism is a spectrum condition. All autistic people share certain difficulties, but being autistic will affect individuals in different ways.

These differences, along with differences in diagnostic approach, means that a variety of terms have been used to diagnose autistic people. Terms that have been used include Autism, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC), atypical Autism, classic Autism, Kanner Autism, Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD), High-Functioning Autism (HFA), Semantic Pragmatic Disorder (SPD), Asperger Syndrome and Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA).

Because of recent and upcoming changes to the main diagnostic manuals, 'Autism Spectrum Disorder' (ASD) is now likely to become the most commonly given diagnostic term. However, clinicians will still sometimes use additional terms to help to describe the particular Autism profile presented by an individual.

Diagnostic manuals

International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10)

The ICD-10 is the most commonly-used diagnostic manual in the UK.

It includes a number of Autism profiles,including atypical Autism, childhood Autism and Asperger syndrome. These are included under the Pervasive Developmental Disorders heading, defined as "A group of disorders characterized by qualitative abnormalities in reciprocal social interactions and in patterns of communication, and by a restricted, stereotyped, repetitive repertoire of interests and activities. These qualitative abnormalities are a pervasive feature of the individual's functioning in all situations".

A revised edition (ICD-11) is expected in 2018 and is likely to closely align with the latest edition of the American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fifth edition (DSM-5)

Although DSM-5 is not the most commonly used manual in the UK it is likely to have a significant influence on the next edition of the ICD. The DSM V has recently been updated and is also used by diagnosticians.

The diagnostic criteria are clearer and simpler than in the previous version of the DSM, and sensory behaviours are now included. This is very useful as many autistic people have sensory issues which affect them on a day-to-day basis. It now includes 'specifiers' to indicate support needs and other factors that impact on the diagnosis.

DSM lists the following criteria as key characteristics of Autism.

A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts, not accounted for by general developmental delays, and manifest by all 3 of the following:

- deficits in social-emotional reciprocity

- deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviours used for social interaction

- deficits in developing and maintaining relationships

B. Restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, interests or activities as manifested by at least two of the following:

- stereotyped or repetitive speech, motor movements, or use of objects

- excessive adherence to routines, ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behaviour or excessive resistance to change

- highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus

- hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment

C. Symptoms must be present in early childhood (may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities)

D. Symptoms together limit and impair everyday functioning

Conditions associated with Autism

Vision and Hearing Loss:

Potential problems with vision and hearing need to be systematically investigated and ruled out.

Anxiety:

This is common in children and young people (YP) with autism. There may be specific phobias or a general tendency towards anxiety. Changes in routine, difficulties understanding a situation, uncomfortable sensory experiences and communication differences can all exacerbate feelings of anxiety. Anxiety can be seen in behavioural changes, appetite changes and changes in sleep pattern. It can also be exhibited in emotional responses, self-injury and reduced school performance.

Select from the Anxiety submenu The NHS Health A-Z - Conditions and treatments

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)/Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD)

The child/YP struggles to pay attention and can show extreme levels of inattention, overactivity and impulsivity, or both. There are also difficulties with organisation and social skills.

http://www.adhdfoundation.org.uk

http://www.livingwithadhd.co.uk

Depression:

Depression can occur in children and young people with autism at all levels of ability. Warning signs can include a change in behaviour, tearfulness, apathy, sleep difficulties, self-injury or aggression. A family history of depression is a risk factor.

https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk

Select from the Depression submenu The NHS Health A-Z - Conditions and treatments

Dyspraxia (Developmental Coordination Disorder):

The child/YP has difficulties in the development of motor coordination. This can include difficulties with dressing (buttons/shoelaces), riding a bicycle, PE and using a pencil. There can also be speech difficulties because of problems coordinating movements of the mouth and tongue. This is called oral dyspraxia.

http://www.dyspraxiafoundation.org.uk

The NHS Health A-Z - Conditions and treatments Select Dyspraxia

The child/YP has seizures (fits). ‘Grand mal’ seizures involve the whole brain and the child/YP loses consciousness. ‘Petit mal’ seizures involve one particular part of the brain and may be simple or complex, depending on which part of the brain is affected.

http://www.epilepsysociety.org.uk

General Learning Difficulties/Learning Disability:

The child/YP’s overall development and ability to learn is significantly delayed.

http://www.mencap.org.uk

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD):

The child/YP experiences repetitive, unwanted thoughts which provoke extreme levels of anxiety. To eradicate the anxiety the child/YP is compelled to perform certain behaviours such as checking switches, doors, hand washing etc.

http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk

Specific Learning Disability:

The child/young person may have difficulties with reading (dyslexia), writing (dysgraphia), maths (dyscalculia) or other particular aspects of their learning while their intellectual ability is age appropriate.

http://www.dysgraphiahelp.co.uk

The child/YP experiences a repetitive and involuntary movements or tics (eg shoulder shrugging, eye blinking, lip smacking etc), vocalisations (sounds or words - eg spitting, throat clearing, swearing, shouting etc) and compulsive behaviours.

http://www.tourettes-action.org.uk

Patterns of deafness

Types of hearing loss

Deafness or hearing loss can occur in one or both ears, can be permanent or temporary and is defined by which part of the ear is affected (type of loss) and by the level of the loss of hearing.

Conductive loss occurs in the outer and middle ear and some can be treated. Sensorineural hearing loss, known as nerve deafness, occurs in the inner ear usually in the cochlea or beyond in the auditory nerve. This is a permanent loss.

Hearing tests are done for each ear by measuring responses to a pure tone signal providing a pattern of the hearing loss, called an audiogram, across the frequencies of human hearing, targeting the areas most important for access to speech. These responses, measured in decibels, are then averaged across 5 speech frequencies and described in more general terms. The British Society of Audiology (BSA) describes hearing threshold levels for each ear by using four bands of hearing loss known as audiometric descriptors. Found in section 9 of ‘Pure-tone air-conduction and bone conduction threshold audiometry with and without masking’

Descriptor average hearing threshold levels (dB HL)

Mild hearing loss 20-40

Moderate hearing loss 41-70

Severe hearing loss 71-95

Profound hearing loss In excess of 95

Where there is a bilateral loss (in both ears) the descriptor for the better ear is used.

However this is a clinical measurement and is not always a reliable indicator of the ability to access sound and communicate in many everyday contexts. BSA says, ‘….they shall not be used as the sole determinant for the provision of hearing support.’

The audiometric descriptor does not convey the impact of a hearing loss from birth which can cause significant difficulty for developing language and communication and hence learning and social interaction.

Impact of hearing loss

The type of hearing loss is significant as is the time of its onset. Many factors impact a child’s language and learning development and there are a variety of education outcomes in children and young people regardless of the level of hearing loss.

As a result of newborn hearing screening in the UK hearing loss is likely to be diagnosed well before any autism. If a baby fails the hearing screening further diagnostic tests within an audiology department take place.

For details of each of the tests see http://www.ndcs.org.uk/family_support/childhood_deafness/hearing_tests/newborn_hearing.html

Auditory brainstem response testing provides information regarding auditory function and hearing sensitivity.

It is often necessary to consider the results in conjunction with further behavioural audiometry whenever possible so that an accurate diagnosis of functional hearing is possible. Diagnostic testing for deafness may require some degree of co-operation and this can present challenges when autism is present but unknown.

There are cases of late onset deafness and progressive hearing loss which may not be detected at the time of newborn hearing screening. One has always to be alert to this possibility and especially when diagnosing Autism per se as indicators for both are similar. eg lack of response to sound, lack of eye contact, poor communicative intent, no shared attention.

In the UK a diagnosis of deafness, regardless of degree of hearing loss, is usually followed by a referral to the local Sensory Support Service. Criteria within the Local Offer of that Authority will determine the support package for the deafness needs of the child

Co-occurring patterns of deafness and autism

Co-occurring patterns of deafness and autism

There are three autism adapted assessments for deaf children and young people that can be accessed through Deaf CAMHS:

Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R)

(A parent/carer structured interview gathering important information about the child)

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Edition 2 (ADOS-2)

(A play and intervention assessment with the child with 5 modules for all age ability ranges)

Social Responsiveness Scale – Edition 2 (SRS-2)

(A screening questionnaire for parents/carers or teachers)

These adaptations are the result of the research Diagnostic Instruments For Autism In Deaf Children Study: DIADS. This study worked to adapt autism assessments to make them more suitable for deaf children and young people, to give better assessments and a more accurate diagnosis, and to support families/carers on the right pathway for their deaf child/young person. The study (funded by the MRC) started in September 2013 and completed in 2021.

Timeline of how the study developed:

The Delphi Consensus – international experts gave advice about the 3 autism assessments to be adapted to make them more suitable for deaf children/young people.

Three autism assessments were translated into BSL for use in the UK.

Families and deaf children /young people were recruited to help test the new assessments.

The data was analysed to see if the adapted assessments worked.

The National Deaf Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services were trained in how to use the 3 new assessments.

An international conference and presentations were held on the subject of Deaf Autism. Three papers were published about the three different assessments.

The results showed that these assessments were as accurate as the assessments available for hearing children. This is the first time these have become available for deaf children.

The papers written about each assessment can be found on Google Scholar:

Modifying and Validating the Social Responsiveness Scale edition 2 for use with deaf children and young people - PLOS ONE Journal

Adapting and Validating the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule

Version 2 for use with deaf children and young people - Journal of Autism and Development Disorders

Adapting and Validating the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised for Use with deaf children and young people - Autism Journal

Contact your local Deaf CAMHS for further help and advice

Webcast overview of comorbid occurrence: powerpoint with live presentation 'More Than Meets the Eye: An Introduction to Autism Spectrum Disorders' using ASL, English subtitles, and voice over.

Diagnosis and Assessment

Autism is not generally diagnosed before the age of 3 years in deaf children and is often not confirmed until as late as 7 or 8 years of age. Advice is to look at milestones to see what is not developing appropriately. If parents/carers or professionals have concerns they should ask early for a referral. Contact your local Deaf CAMHS for help in accessing the adapted autism assessments for deaf children and young people.

Pathways to diagnosis vary across UK Local Authorities. It is vital that there is collaboration between autism and deafness teams to ensure early, accurate diagnosis.

For example:

Pathway to Diagnosis via GP

- Raise concerns with Health Visitor/School

- See GP and ask for referral to Child Development Centre (pre-school age)or Paediatrician (school age)

- Multidisciplinary assessment for pre-school age / Paediatrician Assessment for school age

- Formal diagnosis of autism made

Pathway to Diagnosis via a Specialist Assessment Service

- Raise concerns with Health Visitor/School

- Health Visitor/School refers to Specialist Assessment Service

- Multidisciplinary assessment led by Clinical Psychologist

- Formal diagnosis of autism made

- Follow-up group sessions for parents with members of the Team

Communication

This is a complex area and there is little research available to suggest a ‘best’ mode of communication. As is the case with deaf children, a range of communication modes are likely. The choice will be determined by a range of factors:

- deafness levels

- parental preference

- child’s attitude to wearing amplification equipment to access receptive language

- opportunity for cochlear implantation

- communicative intent

- availability of BSL sign

- school placement and existing mode eg Makaton

- PECS Picture Exchange Communication System

- PODD Pragmatic Organisation Dynamic Display

- AAC Alternative and Augmentative Communication

In some instances several modes will be tried and abandoned; the tensions are: “How long do I continue?”; “Should I use them all?”

Genuine communication demands interaction and taking contingent turns in the conversation. Sometimes an autistic child does not understand what language or sound is for and will be ‘echolalic’ - repeating words and phrases out of context.

Auditory processing

An Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) refers to difficulty processing what is heard. APD is characterised by poor perception of speech and non-speech sounds. APD has its origin in impaired neural function and impacts on life through a reduced ability to listen [BSA APD SIG 2011].

In most cases hearing is normal but sometimes APD can occur in the presence of a hearing impairment. It is more challenging to assess APD in the presence of a hearing impairment. Your audiologist will be able to provide more information about this.

The interdisciplinary APD Service at the University of Southampton is a team of Audiologists, Speech and Language Therapists and Teachers of the Deaf/Educational Audiologists offering guidance on sensory integration, cognition, written language and medical issues, specifically relating to the ear, nose and throat. The team is able to offer interdisciplinary guidelines for the individual, their parents/family and school/workplace and also in-depth assessment and management, if required.

Language acquisition

Just as deaf children will attain different levels of language mastery, it is likely that there is a similar variance with deaf autistic children. Although they may use language successfully in some contexts it is always important to check understanding especially in a social communication context or when it pertains to idioms, emotions and theory of mind.

Sensory issues

The senses: vision, hearing, touch, smell, taste send messages to the brain and help us make sense of our world. We also have senses of vestibular proprioception which helps us know where our bodies are in space and interoception which gives a picture of our internal bodily functions. The brain integrates all of this information and over time we associate these sensations with behaviours and social contexts.

Sensory issues have recently been acknowledged as one of the diagnostic indicators for Autism (DSM V). The wide nature of the autistic spectrum means that the type and degree of sensory issues vary with the individual.

It is important early on in a child’s development to track any issues of this nature and create a sensory profile. If undetected, sensory issues can intensify, resulting in distress and learned behaviour which then becomes more difficult to regulate.

In autistic children it is thought that there is 'different wiring' in the brain. This causes poor integration of sensory information, resulting in experiences which are heightened or lacking. Some children are over (hyper) sensitive. This can relate to some or all of the senses. For example, a child who is hyper-tactile will resist physical touch or textures. Others may be under (hypo) sensitive and may not appear to be aware of the sensation of touch. These children may not even register pain and may seek out physical pressure. Some children develop repetitive behaviours in order to get sensory feedback and can be reassured by the predictability of the same movements. This can give a feeling of security and control. Most behaviour has a function and it is important to establish what that is.

For more on hypersensitivity and hyposensitivity and desensitisation programmes, see Sensory Hyper- and Hyposensitivity in Autism.

At home

As there is little dedicated research in the area of Autism and deafness there is currently very little specific written advice for families. The world wide web has some helpful webinars and charity websites which seek to support families.

It is important that any strategies advocated in any one education/health/social setting are shared with home and vice versa so there is a seamless approach.

A CAMHS booklet ‘Helpful practices for those diagnosed with Autistic Spectrum Disorder’ offers ideas for use in some situations.

Social communication

There are many different types of social communication interventions to improve outcomes for children and young people with autism. Here is an example of one type, Relationship Development Intervention or RDI

Social and emotional wellbeing and mental health

Developing an understanding of self and of others, managing anxiety, and helping to build emotional resilience are vital in reducing vulnerabilities in autistic people.

Autistic children and young people start every day with a high level of stress and can reach crisis point more quickly than their typically developing peers. Around 9.2% of the general population suffers from anxiety – in children and young people with autism this figure is around 40% (National Autistic Society). These numbers relate to having a diagnosis of an anxiety disorder – but many more children and young people with autism live with heightened stress and anxiety that has a huge impact on their everyday lives.

The unique characteristics of autism mean that children and young people are predisposed to higher levels of anxiety than their typically developing peers.

Social difficulties include difficulties understanding other people’s perspectives and difficulties understanding social expectations.

Communication difficulties include problems expressing feelings, needs and wants and in comprehending receptive language

Sensory processing differences mean that responses to sensory information can be very different. Fears of particular sounds, smells and lights may be exhibited.

Rigidity of thought can lead to difficulties coping with changes and new situations, as well as problems finding flexible responses to apparent threats.

All of these issues lead to a cumulative effect – from the outside it can appear that one thing has caused distress but the anxiety has usually been building for some time.

Mental health problems are more common in children and people with autism than in the general population. Mental health problems can lead to even higher levels of stress and anxiety. It is vital that children and young people with autism are supported to find healthy outlets for their anxieties. A document dealing with mental health issues can be downloaded here.

Transitions

Defined as: ‘the movement, passage or change from one position state or stage to another’. Transitions of one kind or another are features of everyday life and can be planned or unplanned. Moving from one activity or place to another can often be difficult for a deaf autistic child causing great anxiety and a meltdown state. The reasons for this could stem from a lack of being in control or not knowing what challenges the ‘next/new environment’ will hold. Or it could be not being ready to relinquish one activity for another that is being imposed upon them.

Strategies to help transition times can be:

-

now and next cards[1]-detailing pictorially the context of each

-

a visual timetable (at different levels of complexity)

-

a sensory diet …physical activities provided by an occupational therapist to desensitize as a preparation for change

-

social stories, comic strips or social storyboards[2] which explain what is going to happen in a given context and enable you to put yourself in that context before the real experience

-

use of an egg timer to prepare for the change.

Autism Education Trust offers a wide range of resources and training

Transition from early years to primary school

Transition from primary to secondary school

[2] The Asperger Children’s Toolkit - these can be purchased from various publishers or via Amazon.

[3] Practical strategies for daily transitions Deaf and Autism Event-Dawn with resources 2015

[4] Impact of music on transitions (Kern Wolery and Aldridge)

Transitions in Education

Moving from one phase of education to another can also present challenges for all children and this is especially so for many deaf autistic children and young people.

Resources to support children moving between schools and from school to college are available.

NAS - National Autistic Society offers a range of advice about moving between life stages.

iPAD app for transition to secondary school

Information about the transfer of audiological management from paediatric to adult services is also available in many areas as a part of the Sensory Support Local Offer. Websearch to find your local authority link in the UK.

Technology

Technology covers a range of amplification such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and bone conduction and bone anchored devices. There is a wide variety of practice and of outcomes in terms of access to sound and functional listening. Outcomes can be shaped by many factors.

There are also assistive listening devices as well as equipment to support communication, learning and quality of life.

Assistive Listening Devices

There are a range of assistive devices which can provide a better sound signal to a listener via a direct connection. The main two are:

Radio aids

A radio aid can often be used to extend the opportunities for hearing sound and can provide a better listening experience over distance as well as emotional support for both wearers and parents. A radio aid consists of a transmitter worn by the main speaker and a receiver worn by the recipient. The closeness of the microphone to the speaker’s mouth and direct transmission of sound (via infra-red, FM, bluetooth) to the receiver’s ear (or hearing device) means they can hear as if the speaker is next to them regardless of the true distance away. There is much research evidence that radio aids benefit deaf children (see Radio Aid MESHGuide)

Soundfield systems

A soundfield works in a similar way for a whole room, delivering an equal sound signal to any spot in a room (within the range of the loudspeaker). There is anecdotal evidence to show that use of Soundfield Systems and personal radio aids can help autistic children focus on what the teacher is saying in classrooms as they promote speech over background noise.

Amplification and deaf autistic children

Currently there are no detailed statistics of children and young people with a dual diagnosis of autism and deafness. Just as deaf children present a varied picture in terms of acceptance and use of hearing devices so it is with deaf autistic children. A small number could be affected by hyperacusis – (intolerance of everyday sound leading to distress) which might cause them to reject any hearing device. Sometimes ear defenders are given to these children. However this is not always considered best practice in the long term and where hyperacusis is a challenge, it is felt that little by little sound needs to be introduced so that a gradual tolerance is built up as sound becomes better understood.

So, as with deaf children, if listening and speaking is the desired outcome wearing hearing devices should be encouraged, even if in short bursts and if lots of re-fitting is needed. One family remember replacing the aids 18 times in one day on their profoundly deaf Autistic toddler. Having used sign language as a baby and been implanted at 4 years he speaks fluently in a clear, intelligible voice at the age of 5 years. Often the child’s tolerance of wearing a hearing aid will contribute to the criteria for receiving a cochlear implant. It is important to ensure that there is a positive experience, something interesting to listen to, which reinforces the point of wearing the device.

The Case Studies section demonstrate some real experiences with equipment.

References:

Thompson N., and Yoshinaga-Itano C. Enhancing the Development of Infants and Toddlers with Dual Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Deafness Semin Speech Lang 2014; 35: 321-330

Tablet technology

Tablet technology is now recognised as a useful tool for a range of purposes. Tablets can be used for motivation and reward.

There is small scale research and a great deal of anecdotal evidence that support use of tablet devices for communication and learning. Many apps have been designed specifically for these.

Some children and young people have a heightened technical aptitude for Information Technology and demonstrate outstanding competence.

Tablet technology and resources which may be useful are available as a download.

Behaviours and stereotypies

These can be varied, significant and hard to manage.

- Play

- Transition

- Socialisation

- Emotions

- Theory of mind

- Language delay

In some children deafness may result in atypical or delayed behaviours. However where autism also occurs in deaf children many of these behaviours have specific characteristics evident in sign, gaze, gesture and voice. They may also be extended in social contexts and heightened to such a degree that they resemble autistic indicators.

Stereotypies

These are self-stimulatory behaviours that refer to repetitive body movements or repetitive movement of objects. This behaviour is common in autism. Some examples are: headbanging, stimming and flapping; spinning wheels on a toy. These are considered part of self-regulating behaviour.

Special interests

These are when there is such a heightened interest that it excludes many others resulting in an unusual depth of knowledge and such a fascination there is a reluctance to leave the object or subject alone. Practice has moved from depriving a child of this special interest to incorporating it into learning and motivation.

Support Strategies

There are many support strategies which have proven helpful but the individual profile will determine which are appropriate and how best to put them into practice. Many do not have research evidence. See Choosing Autism Interventions: A Research Based Guide Bernard Fleming, Elisabeth Hurley and the Goth. Pavilion 2015

Educational Placement

Educational placement in England

Choosing an education setting for a deaf autistic child will depend on several factors. Although parents may wish to choose a local school it is possible that provision locally cannot support the needs of the child. A placement in a resource provision for autism or one for deaf children will depend on the relative needs of each diagnosis. Sometimes a special school placement may be beneficial; compromise is often needed.

It is vital that local Autism and Sensory teams collaborate along with occupational and speech therapies in the best interest of the child.

It is important that both autism and deafness are supported; a peripatetic Teacher of the Deaf may be assigned to a special school or autism provision when there is no expertise in deafness.

Autistic and deaf friendly educational practice

Any education setting must take into account the particular needs of the individual. The levels of autism and deafness as well as cognitive ability will all

shape the teaching and learning programme.

Some general pointers:

- do no harm;

- reduce as much anxiety as possible and build in emotional resilience;

- provide a stress escape strategy- eg room alone; stress toy; weighted blanket

- provide choices and solutions

,; - seek occupational therapy support, working to reduce hyper and hypo sensitivities rather than banning the trigger outright

.; - use visual supports of the appropriate type;

- establish a means of communication and use consistently;

- use routines and social stories;

- offer a quiet area with no visual distraction or peer company if appropriate;

- establish learning style and strengths and work from these;

- careful preparation for all transition times - from lesson to lesson, timetable change, from phase to phase; no surprises;

Sometimes negative behaviours are learned responses to a flight or fright context and they become habitual. Hence it is important to assess early and establish what are the causes of fear and anxiety and reduce them. It is necessary to have regard for the impact on other learners in the context.

Autism friendly classrooms

Autism Education Trust training programme: Autism affects around 1 in 100 children and adults. All professionals working in educational settings should be prepared to support children and young people with autism – and all staff should have a basic awareness of autism and the needs of individuals.

Autism Toolbox is a resource created to support teachers in Scottish schools to make personalized resources for pupils using the structured teaching approach TEACCH. Sometimes all you need is an idea and you can see how to develop and expand it for your own learners.

Practical classroom strategies designed for those with speech and communication difficulties may also be useful.

ICAN provides useful Factsheets:

- Factsheet primarily designed for teachers working in mainstream schools who have children with speech, language and communication needs within their class.

- Factsheet primarily designed for mainstream in secondary schools who may have young people with speech, language and communication difficulties within their classes.

Out and About

Safety is often a concern when out and about both because of deafness but also because the child may have little understanding of danger. Additionally behaviour in an open space is often a greater challenge. parents may be reluctant to expose children to everyday experiences because they may be embarrassed or fearful that their child’s behaviour does not meet social convention.

Social stories can help prepare children for different contexts. Radio aids can help families to stay in speech touch at a distance.

Home

The child at home does not always reflect the child a teacher may see so it is really important for professionals and families to liaise well. Difficulties with sleeping and eating can impact daily life and may need specialist support. Autism and deafness can affect sibling relationships and family dynamics. There are local and national services which can offer support. The web has various sites and fora which seek to offer practical and emotional support generally to families although not necessarily for a specific dual diagnosis.

Early Years

Careful observation and tracking development are the best ways to establish a child’s need so that practical strategies can be implemented as early as possible. This then prevents habitual negative behaviours and anxiety which can be difficult to reverse or replace at a later date. Knowledge of the comorbidity of autism and deafness is increasing, making earlier diagnosis a possibility and greater awareness and acceptance of diversity is growing.

Alternative therapies - Yoga, Music Therapy, Equine Therapy, Dog Therapy

Although not supported by research data, many interventions are successfully used to help autistic children and might also be of benefit for deaf autistic children;

many are outlined in the book: Fleming B., Hurley H., and the Goth (2015) Choosing Autism Interventions A Research Based Guide Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Yoga

If you have evidence please get in touch burwood@ewing-foundation.org.uk

Equine Therapy

Many autistic children find horse riding beneficial

Dog Therapy

If you have evidence please get in touch burwood@ewing-foundation.org.uk

Music Therapy

There is research and anecdotal evidence of the benefits of music for both deaf children and autistic children.

Music Digest is a report by Dr J Galpin looking at the effects of music on children.

Bright Futures School for children with autism. specialises in provision for children with autism and brings a new approach to autism education. The school focuses on the core difficulties that lie at the heart of autism. These include problems with rigid thinking, managing uncertainty and change, social interaction and understanding and managing emotions. These are the difficulties that are at the root of distressed (challenging) behaviour.

Families

There is little dedicated support for families experiencing deafness and Autism outside of that provided by the local offer, DeafCAMHS and web sites.

YouTube National Deaf CAMHS Deaf Children and adolescents with Autism A Guide for Parents and Professionals.

see Resources

Routines

For many autistic deaf children the daily routine is very important. There are numerous ways to present this depending on the age and need of the child. Commercial products are available which can be customised. Its graphical presentation in terms of clutter/colour/contrast/style are considerations. Some websites have free downloadable templates. Customised photos work for some children.

For more about visual timetables visit the ASD teacher website.

Signpost to websites

Signpost to websites and media

Some of these provide regular newsletters

http://www.Autismeducationtrust.org

http://www.Autism.org.uk National Autistic Society (alternative address http://www.nas.org.uk)

http://www.Autismspeaks.org

Presentation in sign with subtitles on dual diagnosis

DVD Asperger Syndrome: A Different Mind University of Cambridge Jessica Kingsley

YouTube National Deaf CAMHS Deaf Children and Adolescents with Autism A Guide for Parents and Professionals

ToD list / forum

The British Association of Teachers of the Deaf hosts an email forum for ToDs and those interested in deaf education and who may seek ideas, opinions and discussion on arange of topics of interest.

If you wish to share information or discussion on Autism and deafness via the Teacher of the Deaf forum you may join the ToD Forum.

Other professionals

National Deaf CAMHS

National Deaf CAMHS is a highly specialised mental health service for deaf children and young people with mental health issues launched in April 2009. The service accepts referrals for assessment of Autism in deaf children and also hearing children of deaf parents. There are now 4 hubs plus 6 outreach services covering England in Leeds, York, London, Taunton, Plymouth, Kent. There is a six-bed inpatient provision in London.

The Leeds National Deaf Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (NDCAMHS) works with children and young people aged 0-18 who have a severe to profound hearing loss, have deaf parents or have BSL (British Sign Language) as a first language and who also experience emotional and/or behavioural issues consistent with a Children’s Global Assessment Scale [CGAS] rating of 50 or less. They work to improve the mental health of these children and young people through supporting them and their families.

Watch a video which features parents describing their experiences of their autistic deaf children.

Signhealth

Signhealth is a deaf health charity with special interest in mental health.

Case Studies

If you have examples you could share please get in touch: exec@batod.org.uk

These will give an overview of children and young people who are deaf and on the autistic spectrum and include a range of successful strategies used with the individual, and those which were not so successful. They are listed in age order.

A draft 'scaffold' Case Study document to assist in producing a case study report is available along with a permission form if photographs and video are used.

Early Years

Early Years Case Study - Child 1

Background

Deafness

Level of Loss – Bilateral moderate to severe sensorineural loss

Diagnosis – Newborn screening

Born at full term following healthy pregnancy. Good delivery – no complications.

Type of equipment – BTE Oticon Synergy hearing aids,

Amount of use – Hearing aid use excellent until two months ago, but currently can no longer tolerate hearing aids at all. Radio aid has been ordered but not able to fit until wearing hearing aids.

Autism

Currently being assessed for Autism.

Presents as having many sensory differences.

Seeks sensory input (loves touching/drinking water, stroking soft materials and shiny surfaces)

Recoils from other sensory experiences (solid foods, dogs barking and the school bell for dinner time)

Struggles to use spoken/signed language to communicate meaningfully.

Is very self directed.

Not interested in playing with her peers – will cry if they approach her to play.

______________________________________________________________

Current:

Age of student: 4 years 3 months

Communication: Can say lots of single words – can name things in home/school book. Cannot use this language to comment on things, ask or answer questions. Uses sign to let parents/carers know some wants. Has recently started to point to things she wants. Is having intensive speech and language therapy as well as signing support.

Type of School Placement: Goes to local mainstream primary. This is the second placement, as first placement did not meet her needs effectively.

Currently applying for EHCP as needs full-time 1:1 TA support – also looking at Autism specific settings.

Typical behaviours: Socially isolated – prefers to be by herself – enjoys looking at books, loves her iPAD (it is problematic to get her off it)

Shows fixed thinking. Easily distressed when things do not go as she has expected eg the journey to the shops is the same as the first part of the journey to the park. If parents go to the shop then she expects to go to the park and will become very distressed if they cannot go to the park.

At school will spend lunchtime alone skipping around the playground and seeking out puddles and collections of rainwater. Needs supervision because she will drink stagnant rainwater.

Greatest current challenge:

- Wearing her hearing aids

- Getting and sharing attention

Sensory issues:

Seeks sensory input (loves touching/drinking water, stroking soft materials and shiny surfaces)

Recoils from other sensory experiences (solid foods, dogs barking and the school bell for dinner time)

Interests: iPad, singing (especially nursery rhymes), dancing

Strengths: Excellent memory, good sense of rhythm, talented singer

Not so Successful Strategies:

Desensitisation programme not successful – investigations into the reason why hearing aids are rejected still under review

Successful Strategies:

Social Stories

Now/Next board

Primary

Primary Case Study - Child 1

Background

Peter is 5 and a half at the time of writing. He was diagnosed deaf at the age of 3. He has a profound loss in one ear and a mild loss in the other. He was given hearing aids and investigations into the cause of deafness and cmv was cited. From the start he was not keen to wear his hearing aids and despite consistent efforts and a desensitising programme he does not wear any amplification equipment. He enjoys wearing a hat.

Diagnosis

He was diagnosed with Autism at the age of 4.

He attended a nursery for hearing children and was placed in a unit for autistic children attached to a mainstream school. He was regularly visited by a ToD and had regular SLT advice and OT advice.

The recommendation was to use PECS more than 40 times a day for him to adopt the system. However this was not consistently used at school and concerns were raised by his ToD that he had no communication system in place or developing.

Typical behaviours and sensory issues

When he gets very excited he flaps getting progressively faster and falls to the ground. When he does not want to do something he runs away or falls to the ground and will kick and cry at length. However he has been seen to comply to a request after this.

It is difficult to anticipate what causes meltdowns as there is not always the same pattern. He has sensory issues relating to food and toileting.

He grinds his teeth much of the time and stills and points to the corner of his right eye when asked to do something. This then moves on to a physical outburst or falling to the floor when the request is repeated.

Communication

He has no interest in communication other than to satisfy his direct needs when he will take you to something but prefers to be independent and for example helps himself to food if he can. Eye contact is rare. Joint attention is limited to an iPAD activity although this is short lived as he tries to take over and move to another app. He is biddable on occasions and will follow an established routine. He is very affectionate with outward signs to his family. He has offered a wry smile to a favourite peer and will play alongside a few chosen ones but not with them.

Greatest current challenge

One of the biggest challenges was toilet training as he was wearing nappies at home and school. This was successfully tackled using a set routine comprising chronological cartoon type line drawings combined with an iPAD with the word ‘toilet’ which he typed when it was felt to be a time as a prompt and also as a need from him.

He has responded to music from the whiteboard, rocking to the rhythm and to music played at a distance into his good ear through a headphone or earpiece held at a distance from an iPAD.

He understands 2 stages of now and next. An egg timer has been successfully used to move him from one activity to another. He will try new things in his own time so a useful strategy is to leave things about for when he is ready.

Interests and strengths

He is fascinated by technology and computers in particular hacking into parents’ details on the tablet. He can retain visual patterns and has a wide graphical vocabulary; when asked to complete a cvc word to match a black splodge (ink) he wrote ‘shock!’. He removed ‘dog’ and ‘cat’ from Proloquo2Go and typed in ‘raccoon’ and ‘horseshoe crab’. He draws well although has an unorthodox pencil grip. He loves the trampoline at home and trips to the beach.

He has an obsession for a time which he defers to whenever he can and replaces this by another eg monsters; alphabet fonts.

After completing a task in the provision, he is happy to spend some time in mainstream on class or parallel activities and shares a teaching assistant experienced with autistic children.

Questions which arose:

Concern from school on how to impact his learning at the pace of his peers?

How long should we encourage him to try his hearing aid?

What is the best form of communication?

What is the correct placement to meet his needs?

Successful strategies:

Use of the iPAD for understanding toileting and to alert the ‘need to go’

Using print to convey meaning and instruction

Egg timers to regulate time spent on an activity and to move him on to the next activity.

Recent outcome:

He has moved to a school for profound and complex needs which is also the outreach base for SI services.

PECs is being used more successfully.

Parents feel confident that his ongoing needs will be met.

Secondary

Secondary Case Study - Child 1

Background

Deafness

Level of Loss – Bilateral moderate to severe sensorineural loss

Diagnosis – At age 4 after investigations following poor speech development. Born prematurely at 32 weeks by emergency section weighing 2lbs 10oz. Spent first two months in Special Care baby unit. Had additional oxygen but not ventilated. Thrived upon coming home after initial period of concern regarding poor muscle tone. This resolved with physiotherapy.

Type of equipment – BTE Oticon Synergy hearing aids, Roger Pen radio aid

Amount of use – Hearing aid use is excellent – all of waking hours. Radio aid use less good – depends on which teacher is in charge at the time.

Autism

Diagnosed at age of 6 years with a working diagnosis of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’.

Reason for ‘working diagnosis’ – could not be sure if language delay was due to hearing loss or Autism. Presented as high functioning, so Asperger’s seemed the best fit.

Struggles socially but is highly intelligent and has learned how to fit in and also what is acceptable and what is not. Struggles with personal care – knowing/feeling when to eat and drink. Struggles to keep track of time and be organised. Has difficulty getting to sleep and has been prescribed Melatonin which helps with this.

Some sensory issues with food textures and clothing.

Current:

Age of student: 16 years 10 months

Communication: communicates orally but can struggle to access/process what other people say – needs additional time. Finds written information very helpful.

Type of School Placement: Goes to a small independent, mainstream school (paid for by Local Authority) which offers a low arousal environment and a number of staff who have specialist qualifications in Autism. Went to local mainstream primary. Has EHCP and had had high level of TA support throughout school career.

Typical behaviours: Finds it very difficult to shift attention from what he is doing to another activity/communication. Can become very defensive and distressed when he is interrupted.