Radio aids – optimising listening opportunities - view as single page

Assistive Listening Devices (ALDs) - radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems - optimising listening opportunities

|

|

Assistive Listening Devices (ALDs) - radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems – optimising listening opportunities

This MESHGuide has been designed to cover a wide range of issues associated with Assistive Listening Devices (ALD) – radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems. It is a resource for anyone who works with children and young people (CYP) who are deaf who may benefit from Assistive Listening Devices (ALD) – radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems. This would include parents, mainstream education settings, specialist education setting teachers and professionals in the field of deafness. It focuses specifically on personal remote microphone technology as an access tool for deaf CYP, and the issues regarding their use. Please note these devices are also referenced as helpful technology for CYP with auditory processing disorder (further information available via the MESHGuide for APD).

The principles supporting the use of Assistive Listening Devices (ALD) – radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems for deaf CYP remain constant; however, the manufacturers are committed to developing and improving each device. The technical advances in remote microphone technology enable deaf CYP, their families, and staff in educational settings, to develop the use of Assistive Listening Devices (ALD) – radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems to maximum advantage.

It aims to be an unbiased source of the latest thinking and research and present relevant case studies on the use of remote microphone technology. It covers what Assistive Listening Devices (ALD) – radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems are, why and how they are used; connection to other technologies; the various types and makes available, with links to manufacturers and other websites.

Assistive Listening Devices (ALD) – radio aids and proprietary remote microphone systems

“Radio aids are known by several different terms, including remote microphones (RM) or transmitters, which are umbrella terms for devices that either use a receiver to connect to the transmitter or pair via Bluetooth. Often, radio aids are now referred to as assistive listening devices (ALDs) or assistive listening technologies (ALTs)”.

“The range of options available and the rapid advancements of hearing technology can make the selection process overwhelming for both professionals and families. The wireless options available can be categorised into two types:

- Universal: Universal options of ALT refer to technology or connectivity options that connect to any hearing technology and are not restricted to specific manufacturers’ models however the only current example of this are inductive loop systems which are increasingly restricted to a few ALD models due to reduction in size and increasing electronic complexity of ALDs. A new system: Bluetooth Auracast was released in December 2023 and will slowly propagate through the mobile phone-TV-Radio- public space areas (please see Auracast section)

- Proprietary: these refer to manufacturer-specific technologies that only work with specific models of primary hearing technologies; or a limited range; the opposite of universal connectivity. Most manufacturers now have these devices including Cochlear, Starkey, GNResound, Oticon and the Phonak Roger system”

(Whyte, S. 2024 Audiology refreshers section 6.4)

Assistive listening technologies (ALTs) are widely used by CYP for developing spoken language, accessing live and recorded voice, in the home and in education, and reducing the listening fatigue experienced when listening in noise. They are also used by deaf adults in professional, social and personal environments. ALTs overcome many of the challenges present in difficult listening situations and help provide deaf individuals with access to speech and sound in a range of environments.

The introduction of AI and mobile phone apps has greatly improved the user experience giving the user the ability to generate personal programs for different scenarios.

The original creation of this MeshGuide has been led by Gill Weston, Cate Statham, Helen Maiden and Pauline Cobbold, all who are (or have been) practising Educational Audiologists and/or Qualified Teachers of Deaf Children and Young People (QToDs). The revision version has been created by members of the Assistive Listening Technology Working Group (ALTWG). They have a wealth of knowledge and been involved with research, setting up ALTs in homes and schools for children with hearing aids, cochlear implants, bone conduction hearing devices and working closely with the manufacturers to solve any problems that have arisen.

ALT is also used by individuals with Auditory Processing Disorders (APD)/listening in noise difficulties. See the APD MESHGuide for information specific to APD.

Disclaimer - the authors have attempted to gather varied examples of research and articles and case studies and are not endorsing a specific viewpoint.

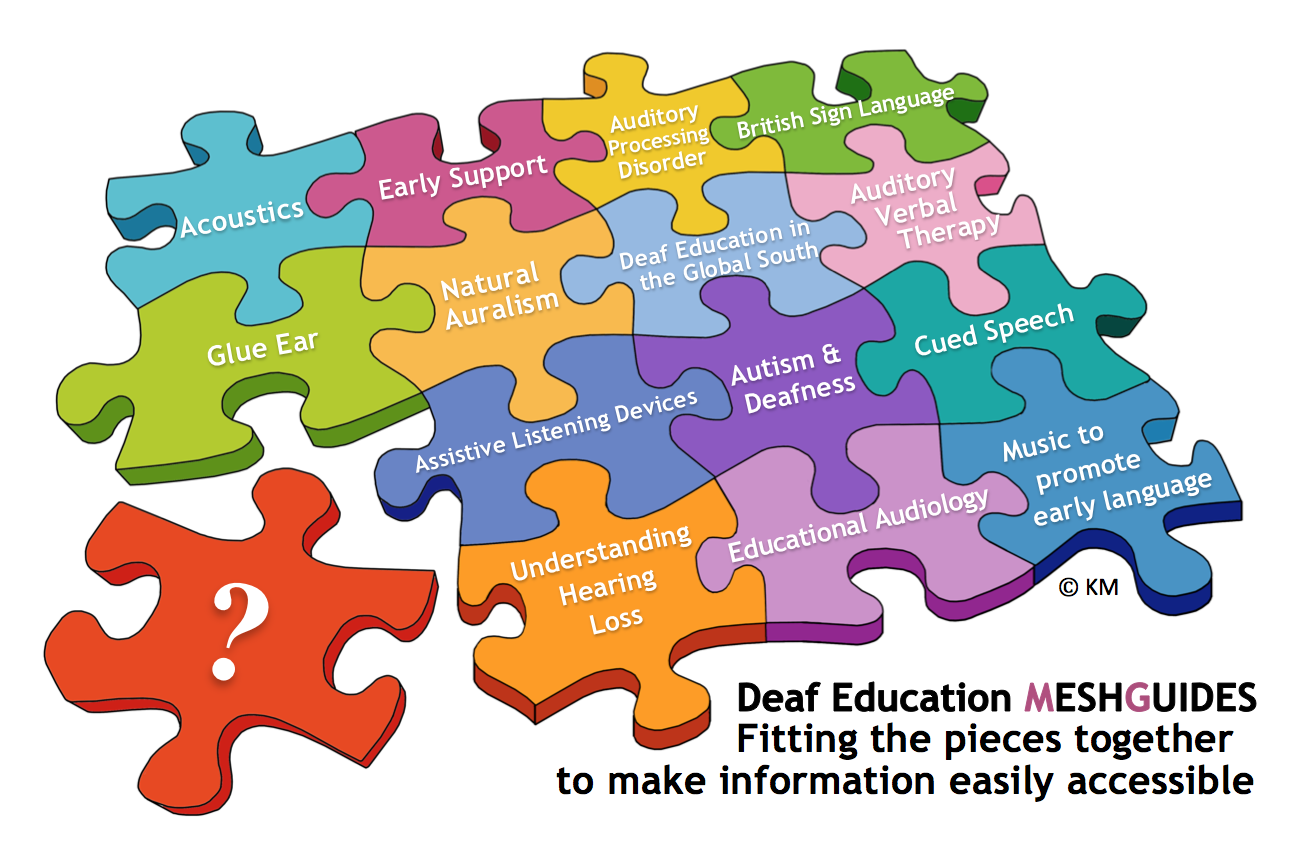

This guide is one in a series of Deaf Education MESHGuides.

Evidence

In this column we list recent research and references on the benefits and uses of radio aids. There is also a section on UK-based Masters research, historic small-scale case studies, showing how individuals have benefited from this technology.

Educational Audiology Association (EAA) publications

Journal of Educational, Pediatric & (Re)Habilitative Audiology (JEPRA), previously named Journal of Educational Audiology, has a range of open-access journal publications.

Useful references: further reading

Listed below are useful references that are not included in the main texts.

BATOD Articles

Articles on assistive listening devices have featured in BATOD Magazines. The Magazines are for BATOD members only. Contact BATOD via exec@batod.org.uk for further information.

Useful references: further reading

Listed below are useful references that are not included in the main texts.

Allen, S., Ng, Z.Y., Mulla, I.M. & Archbold, S. (2016). Using Remote Microphone technology with young children: the real-life experience of families in the UK, British Academy of Audiology, 10-11 November 2016, Glasgow, UK.

Badrak, J. S. (2017). ‘Assistive listening systems in assembly spaces’ The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 141(5): 3781-3781

Benitez-Barrera, C., Angley, G., Tharpe A. (2018) ‘Remote Microphone System Use at Home: Impact on Caregiver Talk. ‘Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research’. 61 pp 399-409

Boothroyd, A (2000). Management of hearing loss in children: No simple solutions. In RC Seewald (ed) A Sound Foundation through Early Amplification. Phonak AG: Stafa

Brannstrom, K., Lyberg-Åhlander. V., Sahlén. B., (2020) ‘Perceived Listening Effort in Children with Hearing Loss: Listening to a Dysphonic Voice in Quiet and in Noise’. Logopedia Phoniatrics Vocology. 47(1) pp. 1-9Busch, T., et al. (2017). "Auditory Environment Across the Life Span of Cochlear Implant Users: Insights From Data Logging." Journal of Speech Language & Hearing Research 60(5): 1362-1377.

Busch, T., et al. (2017). "Auditory Environment Across the Life Span of Cochlear Implant Users: Insights From Data Logging." Journal of Speech Language & Hearing Research 60(5): 1362-1377.Collins, J., et al. (2013). "Deafness and Hard of Hearing in Childhood: Identification and Intervention through Modern Listening Technologies and Other Accommodations." Communique 41(6): 4.

Davis, H., Schlundt, D., Bonnet, K., Camarata, S., Hornsby, B., Bess. F. (2021) ‘Listening-Related Fatigue in Children with Hearing Loss: Perspectives of Children, Parents and School Professionals’. American Journal of Audiology. Volume 30, pp. 929-940.De Ceulaer, G., et al. (2016). "Speech understanding in noise with the Roger Pen, Naida CI Q70 processor, and integrated Roger 17 receiver in a multi-talker network." European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology 273(5): 1107-1114.

De Ceulaer, G., et al. (2016). "Speech understanding in noise with the Roger Pen, Naida CI Q70 processor, and integrated Roger 17 receiver in a multi-talker network." European Eiten, L. R. and D. E. Lewis (2010). "Verifying frequency-modulated system performance: It's the right thing to do." Seminars in Hearing 31(3): 233-240.

Europäische Union der Hörakustiker e.V. (2017) ‘Wirelss Remote Microphone Systems - Configureation, Verification and Measurement of Benefit’. Available at: EUHA-Leitlinie Fitzpatrick, E., et al. (2016). "Children with Mild Bilateral and Unilateral Hearing Loss: Parents' Reflections on Experiences and Outcomes." Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21(1): 34-43.

Fitzpatrick, E., et al. (2016). "Children with Mild Bilateral and Unilateral Hearing Loss: Parents' Reflections on Experiences and Outcomes." Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21(1): 34-43Furno, L. E. (2012). The Effects of Sound-Field Amplification on Children with Hearing Impairment and Other Diagnoses in Preschool and Primary Classes, ProQuest LLC.

Goldsworthy, R., Markle, K. (2019) ‘Pediatric Hearing Loss and Speech Recognition in Quiet and in Different Types of Background Noise’. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. Volume 62, pp. 758-767.

Gustafson, S., Camrata, S., Hornsby, B., Bess. F. (2021) ‘Perceived Listening Difficulty in the Classsroom, not Measured Noise Levels, is Associated with Fatigue in Children With and Without Hearing Loss’. American Journal of Audiology. Volume 30, pp. 956-967.

Inglehart, F., (2020) ‘Speech Perception in Classroom Acoutsitcs by Children with Hearing Loss and Wearing Hearing Aids’. American Journal of Audiology. Volume 29, pp. 6-17.Jacob, R. T. S., et al. (2014). "Participation in regular classroom of student with hearing loss: Frequency modulation System use." CODAS 26(4): 308-314.

Kuppler, K., et al. (2013). "A review of unilateral hearing loss and academic performance: Is it time to reassess traditional dogmata?" International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 77(5): 617-622.

McCreery, R., Walker, E., Spratford, M., Lewis, D., Brennan, M. (2019) ‘Auditory, Cognitive, and Linguistic Factors Predict Speech Recognition in Adverse Listening Condictions for Children with Hearing Loss’. Frontiers in Neuroscience, Volume 13 Article 1093.

McGarrigle, R., Gustafson, S., Hornsby, B., Bess, F. (2018) ‘Behavioural Measures of Listening Effort in School-Aged Children: Examining the Effects of SNR, Hearing Loss, and Amplification’. Ear and Hearing, 40(2), pp. 381-392.Moeller, M., Donaghy, K. F., Beauchaine, K. L.,Lewis, D. E., & Stelmachowicz, P. G (1996). Longitudinal Study of FM System Use in Nonacademic Settings: Effects on Language Development. Ear & Hearing 17(1), 28-41.

Mulla, I., McCracken, W. (2014). ‘The Use of Technology for Preschool Children with Hearing Loss’. Seminars in Hearing. 35 (03), pp. 206-216

NDCS (2017) ‘Quality Standards for the use of Personal Radio Aids’ NDCS London [This publication is currently being updated]

NDCS (2021) Radio Aids, Streamers and Soundfields. Available at: Radio aids, streamers and soundfields | National Deaf Children's Society (ndcs.org.uk)

Rekkedal, A. M. (2014). "Teachers’ use of assistive listening devices in inclusive schools." Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 16(4): 297-315.

Rekkedal, A. M. (2015). "Students with Hearing Loss and their Teachers' View on Factors Associated with the Students' Listening Perception of Classroom Communication." Deafness & Education International 17(1): 19-32.

Sala, E., Rantala, L. (2016) ‘Acoutsics and Activity Noise in School Classrooms in Finland’. Applied Acoustics, Volume 114 pp. 252-259. Schafer, E. C., et al. (2014). "Fitting and verification of frequency modulation systems on children with normal hearing." Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 25(6): 584-591.

Shannan, B. & O'Neill, R. (2022). The views and experiences of deaf young people and their parents using assistive devices at home before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scottish Sensory Centre.Statham, C., & Cooper, H. (2009). Our experiences of introducing FM systems in the early years. BATOD Association Magazine (January), 18-20.

Zaltz, Y., Bugannim, Y., Zechoval, D., Kishon-Rabin, L., Perez, R. (2020) ‘Listening in Noise Remains a Signicant Challenge for Cochlear Implant Users: Evidence from Early Deafened and those with Progressive Heairng Loss Compared to Peers with Normal Hearing’. Journal of Clinical Medicine, Volume 9. Article 1381

Zanin, J. and G. Rance (2016). "Functional hearing in the classroom: assistive listening devices for students with hearing impairment in a mainstream school setting." International Journal of Audiology 55(12): 723-729.

Commercial companies

Case studies

Studies

In 2024, Cooper et al published research on ‘Understanding the sound environments of young children: potential implications for radio aid use’. The objectives of this study were to describe, analyse and compare the sound environments to which deaf and typically hearing children between 3 and 18 months are typically exposed, and identify issues to the development of guidelines for the use of radio aids in this age group. The use of assistive listening technology for very young children is a topic of debate within the UK professional community (audiologists, educational audiologists and QToDs). This study is a recommended read to inform decision making.

UK-based studies

PhD/Masters research publications:

- In 2018 Helen Willis conducted a PhD study on ‘The feasibility of the dual-task paradigm as a framework for a clinical test of listening effort in cochlear implant users’. Helen’s research and lived experience provides useful insights in the area of listening effort.

- Informed Decision Making on Assistive Listening Devices in Early Years (Terry-Short, K. 2023)

- An investigation into the provision of assistive listening devices for deaf children in mainstream schools(Cromack, H. 2022)

Glossary

Assistive Listening Device: ‘Assistive Listening Device’ (ALD), also known as assistive listening systems (ALS) and in the USA, hearing assistive technology (HAT), is used to describe personal devices which help overcome deafness. These can be stand alone or used in conjunction with hearing devices such as hearing aids.

Assistive Listening Technology: Also referenced as Assistive Listening Device (ALD) also known as assistive listening systems (ALS) and in the USA, hearing assistive technology (HAT). These are used to improve ability to hear in a variety of situations where it is difficult to distinguish speech in noise. The three main technologies use induction loops, infrared and radio frequency (RF). The latest ALDs are wireless and use the same 2.4GHz technology platform as is used with Bluetooth and Wi-Fi devices.

Assistive Listening Technology Working Group (ALTWG): Previously known as the UK Children’s Radio Aid Working Group, and prior to that as the FM Working Group. This was set up to encourage developments in the field of assistive listening technology, promote good working practice and to share information.

Attenuator: This reduces the strength of an audio signal. Used with a stetoclip when listening and checking powerful hearing aids so the listener’s hearing is not damaged.

Audible: a sound which is able to be heard.

Audiology refreshers: An open-access resource published by BATOD that has been designed to support professionals working in deaf education, audiology and technology to access new and updated content on

- Anatomy and physiology of the ear

- Aetiology and types of deafness

- Auditory perception and hearing testing

- Acoustics and physics of sound

- Listening skills and functional hearing

- Hearing technologies

Auracast: Auracast is set to augment telecoil connectivity, streaming audio output to hearing devices. Released in December 2023 a number of phones and systems are now available, and these will slowly expand. It can be added to many existing telecoil/loop systems. Auracast is a broadcast system (i.e. one to many) and is aimed at public spaces, theatre’s etc plus personal use TV streamers etc: please view this PDF link to Mark-Laureyns' presentation 'Auracast-Where are we now?'

Unlike telecoil it can have many channels i.e. multiple languages at an airport, selected via an Assistant” which currently may be an app or QR code.

Devices compliant and tested to the Bluetooth Auracast specification (these carry the Bluetooth Logo) must have the 16-24KHz channels which are suitable for the majority of Auracast enabled ALDs, the higher quality channels will not be audible to most but not all hearing aids.

BCHD: Bone conduction hearing devices can be fitted when there is a purely conductive deafness, e.g. glue ear, long-term middle ear problems, or when behind-the-ear (BTE) hearing aids are not appropriate, eg microtia, atresia, or for single-sided deafness (SSD). Young children tend initially to wear it on a softband. It can also be fixed to an implant in the skull which is inserted under surgery. For further information visit BATOD Audiology Refreshers Section 6.2

BATOD: British Association of Teachers of Deaf Children and Young People (BATOD) is the only professional association for Qualified Teachers of Deaf Children and Young People (QToDs) in the UK representing the interests of QToDs and other professionals working with deaf children and young people.

BATOD Foundation: BATOD Foundation closed in 2021.The BATOD Foundation was a research, training and information-based charity dedicated to improving the life chances of deaf children and young people by disseminating the outcomes of research projects supported by the Foundation. BATOD Foundation led on the creation of the MESHGuides for deaf education.

British Association of Educational Audiologists - British Association of Educational Audiologists (BAEA) is the only professional association for Qualified Educational Audiologists in the UK representing the interests of Educational Audiologists and other professionals working with deaf children and young people.

BKB sentence test: Lists of 10 sentences, each containing 50 key words put together by Bamford Kowal and Bench (BKB) for testing the ability of deaf children (usually >8 years old) to hear words in sentences. The test is scored by asking the child to repeat the spoken sentence and identify the correctly spoken target words. The final score is the number of correctly identified words from the list of 50 expressed as a percentage. The test can be administered in quiet conditions or in the presence of background noise.

Bluetooth Special Interest Group: This group is the organisation that oversees the development of Bluetooth technology and the testing and licensing of the Bluetooth technologies and trademarks to manufacturers.

Cochlear implant: “A cochlear implant is an electronic device which may be suitable for children and adults who receive little benefit from conventional hearing aids. Conventional hearing aids work by making sounds louder.

A cochlear implant is different because sounds are turned into tiny electrical pulses, which are sent directly to the nerve of hearing. The implant can therefore bypass some of the inner ear structures which are not working. Naturally it is important to remember that no electronic device can be expected to restore function to the levels experienced by a normally hearing ear.” (British Cochlear Implant Group)

British Cochlear Implant group: British Cochlear Implant Group (BCIG) is a group of health care professionals and other interested parties in auditory implant provision in the UK.

dB: A decibel is a measurement which indicates how loud a sound is. The healthy human ear can hear approximately between 0dB and about 140dB. The smallest audible sound is about 0dB – silence, but a sound which is 1,000 times more powerful than silence is measured at 30dB. Normal conversation is measured at about 60dB

Deafness: Deafness (temporary/permanent) also known as hearing impairment, is a partial or total inability to hear. It may occur in one or both ears. Temporary deafness, usually a conductive type of deafness, occurs when sound cannot pass through the outer and/or middle ear to reach the cochlea and continue along the auditory nerve. This can be caused by a variety of conditions and can be temporary or permanent. This type of deafness may be managed with hearing aids or grommets. Some CYP may have a more permanent type of conductive deafness which may fluctuate in hearing levels because of persistent infections. A sensorineural deafness is permanent. This type of deafness occurs when the hair cells inside the cochlea are not working correctly, or when sound cannot travel along the auditory nerve effectively. This type of deafness is permanent and may worsen, depending on the cause. Sensorineural deafness may be managed with hearing aids or cochlear implants (CIs), according to hearing thresholds.

Direct input shoe: This allows direct connection of a hearing aid to other audio equipment. Often called a shoe or boot. They are specific to the make and model of each hearing aid. These are becoming less common as receiver technology becomes built in to the hearing device.

Educational Audiologist: A Qualified Teacher of Deaf Children and Young People who also has an additional qualification in audiology working in an education support service or school for the deaf.

Educational Audiology Association: The Educational Audiology Association (EAA) is an organisation that aims to connect and support an international organisation of audiologists and related professionals who deliver a full spectrum of hearing services to all children, particularly those in educational settings.

Equality act – Legislation passed by the UK Government in 2010 and protects people from discrimination in the workplace and in wider society.

It replaced previous anti-discrimination laws with a single Act, making the law easier to understand and strengthening protection in some situations. It sets out the different ways in which it’s unlawful to treat someone. Equality Act 2010: guidance - GOV.UK

ETSI: The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) is an independent, not-for-profit, standardisation organisation in the telecommunications industry producing both Harmonised standards for placing equipment on the European (including UK) market and many other radio and communication based specifications.

Hearing: Hearing, in humans, is the ability to detect and perceive sound using ears, which is then transmitted to the brain.

Inverse Square Law: In this MESHGuide, this applies to the reduction in the volume of sound when the distance from the source is increased. The sound intensity is reduced in an inverse proportion to the square of the change in distance. For example: if the distance is doubled 22 = 4, the inverse of 4 is ¼ therefore the signal is one quarter of the original volume when it reaches the listener’s ear.

Intelligibility: In the context of speech, intelligibility refers to the amount of the speaker’s output which can be understood. This will be affected by background noise.

Listening: Listening requires effort from the listener and is a conscious processing of sound. It involves complex affective, behavioural and cognitive processes.

Listening fatigue: “It is normal, natural and healthy to experience listening effort. However, if listening effort becomes too high for too long, this can cause “cognitive overload”. This is where the brain becomes overwhelmed and will start to struggle to process any new information.” “Dr Helen Willis ‘‘Go for Gold’ strategy’ Go for Gold_CHILDREN/Go for Gold_ADULTS

LA: Local Authority is responsible for providing amongst other services, education, in a particular area of the UK. Education Authority in NI

Latency: The time taken for a piece of electronic equipment to respond to commands or changes in conditions. This can affect the user’s enjoyment.

MCHAS: Modernising Children’s Hearing Aid Services. Good Practice Guidelines.

NDCS: The National Deaf Children's Society: a charity dedicated to creating a world without barriers for deaf children and young people.

Parrot and Parrot plus: Portable automated speech tests using digitally and balanced male and female human voices.

Personal radio aid: A device comprising a transmitter, which the speaker wears, and receivers which the child or young person wears. These make speech more audible in difficult listening conditions, such as background noise, reverberation and distance.

Quality assurance: The checks used to ensure that a product or service meets the specified requirements.

Radio aids: Radio aids are known by several different terms, including remote microphones (RM) or transmitters, which are an umbrella term for devices that either use a receiver to connect to the transmitter or pair via Bluetooth. Often, radio aids are now referred to as assistive listening devices (ALDs) or assistive listening technologies (ALTs). They allow sound to be transmitted directly to the users’ hearing device(s), overcoming the difficulty of listening in background noise and at a distance.

Receiver: The part of the personal radio aid worn by the CYP. It can be body worn, attached to hearing technology by wires; ear level, attached directly to the hearing technology; integrated, part of the hearing technology itself or using a personal neckloop.

Integrated receiver: a receiver which is built into the hearing device rather than added on as an accessory.

Reverberation: The persistence of a sound after its source has stopped which is caused by bouncing of sound waves off hard surfaces before reaching the listener’s ear

Code of Practice:

Wales The Additional Learning Needs Code for Wales 2021

SEN: Special Educational Needs. The SEN Code of Practice suggests four main areas of special need: Cognition and learning; Behaviour, emotional and social development; Communication and interaction; Sensory and/or physical needs.

SEND: Special Educational Needs and Disabilities

Soundfield system: An amplification system that evenly distributes the teacher’s voice around the room, using a microphone and speakers thus enabling pupils to hear equally well regardless of where they are seated or which direction the teacher is facing.

Speech in Noise tests: Evaluation of personal radio aids and hearing aid technology is important. Speech testing in quiet and babble noise is used quite routinely. There are a range of tests available for different age groups, each with its own standardised systematic approach.

Speech intelligibility: In speech communication, intelligibility is a measure of how comprehensive and understandable speech is in given conditions. Intelligibility is affected by the quality of the speech signal, the type and level of background noise, reverberation and the properties of the communication system used.

SPiN or Speech in Noise tests: Speech is presented in quiet and with varying levels of background noise to ascertain the difficulty the child has in understanding the speech in the presence of noise. Sentences or single words can be used.

Stetoclip: A device which can be used by a hearing person to listen to a hearing aid to make sure it is working, see also attenuator.

Test Box (HIT): This is a sound treated enclosure which gives accurate repeatable measurements of a hearing aid and its functioning. It is also used by QToDs and Educational Audiologists to monitor the function of hearing aids and to ensure that when a radio aid is fitted, it is balanced with the hearing aids, so the sound level received gives the desired advantage and the CYP has a good listening experience.

QToD /ToDs: A Qualified Teacher of Deaf Children and Young People is a qualified teacher who has an additional mandatory qualification in teaching deaf children and young people.

Transmitter: This is the part of a personal radio aid system which is worn or held by the person talking, it can also be plugged into a TV/audio source.

Assistive Listening Technology Working Group – formerly The UK Children's Radio Aid Working Group and FM Working Group: This was set up to encourage developments in the field of personal radio aids, promote good working practice and share information.

BATOD Audiology Refreshers

In May 2022, BATOD jointly funded with William Demant Foundation, a revision of the BATOD Audiology Refreshers as an open-access resource BATOD. In partnership with DeafKidz International (DKI) who are coordinating the project, along with the British Society of Audiology (BSA), the lead partner, BATOD published the live resource in October 2023.

Section 6.4 has content specific to assistive listening devices.

What and Why?

This column provides information on what radio aids are and how they can be used to support children’s learning. The criteria for issuing such a system is discussed and suggestions on good practice are given. This includes provision for babies and preschool children.

This column also looks at the listening environment for children and young people (CYP) and how radio aid systems can be used to support CYP in such environments that might otherwise be detrimental to their listening and to their learning.

What are assistive listening devices?

There is a range of ALDs available, and a personal radio aid or propriety microphone device might be recommended in educational and/or home settings.

They have the potential to greatly enhance deaf CYP’s listening experiences by making speech more audible in situations where distance, background noise and reverberation make listening difficult. The radio aid works by making the sound/speech the CYP needs to hear, such as the teacher’s voice, clearer in relation to unwanted background noise and helps to overcome the problems of hearing speech at a distance.

In this NDCS YouTube video a deaf young person describes what a radio aid is.

An ALD might consist of a transmitter, worn by a speaker (e.g. teacher, peer or parent) and a receiver/s, worn by the CYP.

There are different types of receiver/s:

● Integrated receivers are either built into the hearing aid or attached directly to the hearing aid/cochlear implant speech processor. If built-in, they may require activation by a transmitter.

● Ear-level receivers are attached to hearing aids and cochlear implant speech processor/s using a direct input shoe.

● Neckloop receivers which require the T programme to be enabled on the CYPs hearing aids or speech processor/s.

● Headphones or a personal soundfield for CYP who don’t use a hearing aid.

The NDCS have produced a comprehensive webpage designed for parents on assistive technology including radio aids.

Section 6.4 of the BATOD Audiology Refreshers highlights the differences between universal and commercial proprietary ALTs, the different connectivity technologies, and options available for each of them.

“The range of options available and the rapid advancements of hearing technology can make the selection process overwhelming for both professionals and families. The wireless options available can be categorised into two types:

- Universal: only T-coil and Auracast are universal

- Proprietary: All major manufacturers now have various remote microphones

Why use assistive listening devices?

Assistive listening devices (ALDs), also known as assistive listening technologies (ALTs) can provide a much-needed option for deaf children and young people (CYP) to access speech and sounds.

Modern hearing aids, bone conduction hearing devices and cochlear implants allow most wearers to hear quiet speech when the listening situation is quiet, the speaker is in close proximity and with a known speaker. However, in reality, the world is a noisy place, and a great deal of communication takes place in less-than-ideal listening situations. There will be times when a CYP may struggle to hear.

These devices work with a CYP’s hearing aid or speech processor to make it easier for them to listen to and concentrate on the sounds or voices they need or want to hear, particularly when there is background noise or other distractions in the environment.

These devices help to overcome the problem of distance by bringing the speaker’s voice right into the listener’s ear. Microphones on hearing aids and speech processors work best at a distance of around 1-3 metres but CYP are not often at this critical distance from the speaker. Sound energy decreases the further away from the source one goes. The doubling of the distance will result in a decrease in 6dB. This is known as the Inverse Square Law.

Criteria

Any deaf CYP should be considered a candidate for an assistive listening device.

The Quality Standards for the use of personal radio aids

Quality Standards 1 (QS1) states:

‘Every deaf child should be considered as a potential candidate for provision with a personal radio aid as part of their amplification package, at first hearing aid fitting. This position requires that providers ask why a deaf child should not be considered as a potential candidate for a personal radio system, rather than which child should. It also highlights the need for a close working relationship between health and education teams. Some children who have normal hearing thresholds, and who don’t use hearing technology (for example, those with auditory processing difficulties), may also benefit from a personal radio aid. You should consider the following essential factors when determining a suitable candidate for a Radio Aid.

● Recent research suggests that even very young children and reluctant hearing aid users can get significant benefits from using radio aids.

● Children should be encouraged to understand the effect of distance on sound, and of localisation as part of their listening development whilst using radio aids.

● Appropriate support and training are needed to ensure those in the child’s environment can support the best use of radio aid technology. Contexts for candidacy and other factors for consideration can be found in the Good Practice Guide for radio aids.’

In 2024, Cooper et al published research on ‘Understanding the sound environments of young children: potential implications for radio aid use’. The objectives of this study were to describe, analyse and compare the sound environments to which deaf and typically hearing children between 3 and 18 months are typically exposed, and identify issues to the development of guidelines for the use of radio aids in this age group. The use of assistive listening technology for very young children is a topic of debate within the UK professional community (audiologists, educational audiologists and QToDs). This study is a recommended read to inform decision making.

Using radio aids with preschool deaf children

This is a study conducted by The Ear Foundation. Twenty one families were recruited to explore the benefits and challenges of ALD use with a deaf child aged 4 years and under. Findings provide strong evidence for the advantages of early fitting of ALD and support equitable access, consistent protocols and funding.

Ian Noon (NDCS) refers to this research in his article on Radio Aids in the Early Years, in the May 2018 BATOD Magazine. He also reports on the work of the NDCS to widen availability of radio aids in the early years.

Listening in noise

The aim is to ensure that all CYP and especially those who may have a temporary or permanent deafness and those with auditory processing/listening in noise challenges can listen and learn effectively in their educational setting. How intelligible speech is to a CYP will depend on how background noise can be reduced or eliminated and the acoustic quality of the educational setting, ie how much sound reverberates (or echoes) around the room. The greater the reverberation, the less the CYP will be able to hear the person speaking. Speech intelligibility will also depend how teaching styles are changed to the listening requirements of CYP.

It is important that the listening environment is as good acoustically as is possible. The evidence column of the Acoustics: listening and learning MESHGuide gives further information and research on the importance of good acoustics within classrooms.

Soundfield systems can be used in the classroom, as a benefit to all children listening in noisy situations. Radio aids can be connected to a Soundfield system to further enhance speech intelligibility of the deaf CYP.

Anne Bailey explored ‘A Comparison Between Two Different Speech in Noise Test Setups’ in her Masters study.

Supporting listening difficulties

There are some CYP who do not have a measurable level of deafness but find listening to and processing information difficult. Assistive listening technology can be a useful tool for these CYP. The research below gives examples.

The MESHGuide for Auditory Processing Disorder (APD) outlines specific reference for APD.

This video shows how hearing aids and a radio aid helped a girl with auditory neuropathy

Rance, G. (2014). "Wireless technology for children with autism spectrum disorder." Seminars in Hearing 35(3): 217-226.

Good practice

The Assistive Listening Technology Working Group formerly known the UK Children's Radio Aid Working Group, working with the NDCS, produced the Quality Standards for the use of personal radio aids. This is a resource for those who commission services for deaf CYP, practitioners who work with them and manufacturers. It aims to provide realistic and attainable quality standards and describe good practice for the selection, fitting, management and evaluation of radio aid systems for CYP.

There is also a Good Practice Guide, accessible on the website, on the ‘Quality Standards 2017’ tab which gives practical ideas on how to attain the Quality Standards.

See also ‘Routine Checks’, ‘Use in Educational settings’ and ‘Use in everyday life’ in this MESHGuide.

How?

This column is intended for parents and professionals. It explains how to ensure that you and the deaf CYP get maximum benefit from their assistive listening device. It is recommended that you seek training from a qualified professional ie Educational Audiologist, Qualified Teacher of Deaf Children and Young People, prior to use.

Routine checks

The hearing aids, bone conduction hearing devices, speech processors and assistive listening devices should be checked at regularly, ie at least daily if the child is not yet able to report faults with the system, and at a frequency that is agreed with the young person/parent who have established checking routines. This will ensure that they have the best possible signal to hear the speaker's voice.

- Look at the hearing aid and assistive listening device, is there any damage?

- Check the batteries in the hearing aids.

- Listen to the hearing aid using a stetoclip with an attenuator.

- Attach the assistive listening device.

- Give the transmitter to another person or place by a sound source.

- Listen to the sound through the whole system.

- Use the Ling sounds to check that the CYP can discriminate speech sounds through the system. Read Section 5.1 BATOD Audiology Refreshers for further details about Ling sound checks.

- Validation of device setup using speech in noise testing.

- If you are concerned go to the troubleshooting section in the next column

How radio aids can help - A guide for families (NDCS publication), gives a full description (pages 30-34) of how to check the systems daily, how to look after the system, and how to explain the use to teachers.

The NDCS also produced a video on how to check your radio aid system

Use in educational settings

Hearing loss in the classroom is a video that demonstrates the effect of using a radio aid in the classroom.

Before the lesson begins

- Ensure teacher is wearing transmitter and it is charged and switched on.

- Ensure pupil is wearing receivers and they are connected correctly.

- Check that the microphone is in the correct position - 15 cm from mouth.

- Discreetly check with the pupil that the system is working.

- If using more than one transmitter, check the others are working too.

- Connect to soundfield system if using one.

During the lesson

- Deaf pupils still need to see your face while you are talking. Avoid being in shadow as this makes lip reading difficult.

- Only one person should speak at a time.

- Pupils contributing to the lesson should use the transmitter. If this is not possible the teacher should repeat the contribution to ensure the deaf pupil has heard clearly.

- Mute the microphone when not talking to the deaf pupil, to avoid them overhearing irrelevant topics or conversations.

- If appropriate, pass the transmitter to other pupils for small group work.

- Keep background noise to a minimum. The noise will still be picked up by the microphones on the child's hearing aids and conflict with your voice.

Ten Top Tips for mainstream teachers using a radio aid transmitter in the classroom

- Switch the transmitter on when talking to the whole class or group in which the deaf child is taking part.

- Remember to switch the transmitter off if you or the child leaves the room otherwise, the child will still be able to hear you or there may be interference as the receivers try to ‘find’ the transmitter.

- Help the child to choose an appropriate place to sit without unnecessary disturbances or distractions.

- If using a soundfield system along with the radio aid, make sure both are working and that they are connected to each other.

- Test the range of the radio aid system with the child so you can be sure that they can always hear you and so that you are aware of any limitations in your classroom.

- Switch the radio aid off, or mute the microphone/transmitter, if you go to speak to a group of other children which does not include the deaf child, or when having a conversation that the deaf pupil doesn’t need to hear (the signal can travel some distance and even through walls), when going on a comfort break or when leaving the classroom.

- Avoid standing in a noisy place, close to any noisy equipment or near an open window, as the microphone can pick up background noise and transmit this to the deaf child.

- Avoid letting the microphone knock against your clothing or jewellery as this will create noise through the system. This can affect the child's listening skills if it happens often. They stop listening and the effectiveness of the system diminishes.

- Remember to put equipment on charge at the end of the day, even if it has not been used for every session that day. It is more effective to charge equipment routinely every night rather than ‘only when it needs to be’. This could also result in it not being charged ready for the morning or running out of power in the middle of the day!

- Remember not to go home wearing the radio aid transmitter (it is surprisingly easy to do).

(Adapted from the NDCS booklet - ‘How radio aids can help - A guide for families’)

In addition, if a child has removeable receivers ensure they are removed at the end of the session and stored safely until needed again.

Use in everyday life

Assistive listening technology can be very useful in everyday life, including access to online gaming and other media content. Deaf CYP often find themselves in difficult listening environments eg toddlers in pushchairs, horse riding, bike riding, the car, supermarket, music and drama rehearsals, listening to music, phone, TV, restaurant, cafe, the park.

Top tips

Engage directly with the CYP as appropriate.

- Seek advice from a qualified professional prior to use, to ensure the system is set up appropriately.

- Check battery is charged, and the system is switched on and working.

- Wear the microphone 15cm from your mouth.

- Remember to mute the microphone when you don't want the child to hear what you are saying.

- Remember that the microphone is sensitive and that rubbing from jewellery, lanyards and clothing can cause unwanted noise.

- Remember the child will not be able to tell where the voice is coming from, unless they can see you talking.

- Call the child’s name to get their attention before talking to them.

- The signal may be poor if there is an obstruction between the transmitter and receiver.

- Be aware that the system works best within a certain distance. See manufacturer's’ recommendations.

Costing and funding

The NDCS publication explains about your rights in the UK, for getting a Radio Aid for your child (page 35). Parents of CYP in independent schools who are not supported by the LA, may have to fund it themselves.

Insurance

The equipment is getting smaller and easier to lose, discuss with your provider about replacements and insurance. As receivers are often installed into hearing devices they are also lost if the hearing device is lost which can have a financial implication. However, this should not be a barrier to fitting and use.

The NDCS issued a Position Statement in 2018, entitled ‘Charging and insurance to cover the cost of replacing or repairing of all hearing and listening equipment provided by NHS and local authorities’.

Some insurance providers are experienced with assistive listening technology eg Aspen Associates' Insurance.

Choosing a system

There are a variety of assistive listening device systems available. It is a good idea to discuss the choice with your QToD or Educational Audiologist as there are a number of considerations.

- Some systems are incompatible with some hearing aids.

- Some systems are not compatible with other systems, and this can lead to complications for your CYP in their educational/home environment.

- Systems have different features that make them more or less suitable.

- The technology is improving all the time, so it is advisable to check the latest models.

- The different manufacturers have websites which give the relevant information.

- Have a practical demonstration of the system.

Manufacturer websites

The main manufacturers for paediatric hearing aids on the NHS are GN Resound, Oticon and Phonak. To gain more detailed information on each specific model, select the manufacturers via the Connevans dedicated ‘My Hearing Aid‘ webpage.

The main manufacturers for paediatric cochlear implants on the NHS are Advanced Bionics, Cochlear and MED-EL. To gain more detailed information on each specific model, select the manufacturers via the Connevans dedicated ‘My Cochlear implant’ webpage.

The main manufacturers for paediatric bone conduction hearing devices on the NHS are Cochlear and Oticon Medel. To gain more detailed information on each specific model, select the manufacturers via the Connevans dedicated ‘My Bone conduction hearing aid’ section of their webpage.

Troubleshooting

Here are some suggestions for when things go wrong.

- Turn it off and on again.

- Check the batteries in system, adaptors and hearing device.

- Check the receiver is connected to the transmitter?

- Is there another transmitter nearby which could cause interference?

- Is there anything blocking the way between the transmitter and the receiver?

- Are the receiver and the transmitter within the transmission range?

- Change the shoe/connecter.

- Check transmitter is not on mute.

- Check the cable and connections. Are they in good order? Are they the right ones for your device?

- See the manufacturer's user guide.

Connecting to other technology

Hearing devices can be connected to a variety of other technology to give the CYP direct access to eg mobiles, gaming consoles, TV, iPad or tablet, mobile phones, smart board.

Some assistive listening devices can be used to do this, either by bluetooth or using direct input leads.

The Connevans website allows you to see the technology that is compatible with your hearing aids

Connection of ALD to External Accessories

Most instruction books only give a few pictorial instructions for connection of ALD or Cochlear Implants to phones-computers etc which gives the impression this is an instantaneous activity whereas some connection may take 15 minutes to achieve, unfortunately the devil is in the detail and the objective of this document is to provide a more detailed description of such connections and the complications which may arise

Please be aware that any form of streaming will deplete the battery life of the ALD.

Mobile Phones

The most common connection used is Bluetooth, which comes in three main forms:

- Classic: which almost every mobile phone has and is also used for wireless headphone, earbuds and connection to computer audio etc. Bluetooth SIG regularly issues updated versions and older mobiles phone or specific models may not be compatible with the ALD software.

- LE or low energy: not many models of phone currently have this, manufacturer’s using LE will have a list of suitable phones or an external unit which converts the ALD transmission to classic.

- Auracast: released in late 2023 and not yet commonly available on phones (as at October 2024), whereas Bluetooth Classic and LE are a one to one link Auracast is a broadcast, i.e. one to many BUT the linkage will depend on the transmitter manufacturers “assistant” which is the software app controlling access to that transmission which is currently under the control of the manufacturer’s design. Also, an ALD manufacturer may “lock” their accessories to their own ALDs

If problems are experienced which cannot be overcome by information in this document most ALD manufactures have a list of phones which can be used with their device.

When connecting an ALD to a phone for the first time it is best to switch off any Bluetooth transmissions in computers-mouse-headphones -wireless speakers and some HiFi and radios etc or physically separate the ALD and phone by going outside or into another room.

When the phone is placed in search mode for “pair new device” it will pick up any other Bluetooth device in range and most, such as a PC will have relatively powerful transmissions compared with the ALD, therefore it may require a number of repeats of the “pair new device” before the ALD is found

A further complication is to ensure the ALD is in pair mode as most have a time limited transmission.

And of course, the ALD has a fully charged battery.

Once the ALD is “found “it may take some time before it has a full connection as there is often an extensive exchange of data to ensure the phone and ALD software are compatible

Warning: when programming or pairing ALD is best to keep away from laptop or PC as they generate a strong magnetic and EMC field which may generate damage to the ALD software

An ALD may have two connections to a mobile phone:

- To a manufacturers app

- To the phone for audio from phone calls music etc

In most cases pair the ALD with the phone before attempting to connect to the app.

In the case of an external device between the ALD and phone pair the external device first

In all cases as described above this may be a protracted activity. It can take in excess of 15 minutes to achieve full connection.

TV Streamers

These will mainly use some form of Bluetooth (including Auracast), and the pairing issues identified above are relevant.

Audio Connection

These require a connection to the TV audio output which used to be a simple connection to Philips/RCA connectors or if daisy chained from HiFi a simple doubler, however most modern TVs only have an optical or HDMI connector.

Optical: Doublers or treble units are available using the description to search: Digital Audio Optical Cable 1 in 2 out Toslink Splitter Dual Port Audio Adaptor

HDMI: A converter from RCA to HDMI are available using the search description: RCA to HDMI Adapter.

RCA to HDMI Adapter: Please note these require a 5V power source please

Companies, such as Connevans can advise on these items .

Frequencies and transmission

Sometimes there can be interference or a break in the transmission.

● A clear line of sight between the transmitter and receiver(s) will give best results.

● Hiding the transmitter behind books, tins etc will decrease coverage dramatically irrespective of frequency of transmission.

● Be aware when using the system outdoors, that obstructions and weather can get in the way of the signal from transmitter to receiver.

● Within a room, blind spots will occur if a metal structure or other obstructions are between the transmitter and receiver.

Below are some frequently asked questions - and answers - about radio aids and transmission of signals.

1.The building has a mobile phone mast on top.

a) will it cause a health hazard? No, there is an umbrella protective effect see Ofcom results at:

b) will it interfere with the radio aid? No

2. Will the assistive listening device present a health hazard? No

3. Will the WiFi interfere with the device? Extremely unlikely but the radio aid system may cause the WiFi reception to reduce. In which case move the WiFi.

4. Can I run radio aid systems in adjacent rooms/classrooms: YES, but discuss with your supplier as minor technical adjustments may be required.

5. Are all manufacturers’ systems compatible? Not in every case. Also, some accessories may not be compatible with all ALDs made by the same manufacturer: always check.

6. I have completed all the checks, but I still cannot hear through the system. Check you are not shielded from the transmitter aerial location.

7. Does the signal drop as batteries decline? No - the radio aid has a battery limiter which shuts off the system when the battery level drops below a certain point (normally there is a bleep to warn that the battery is fading).

8. Does the signal normally fade away at a distance, cause distortion of ‘voice’ or just drop off? A Digital transmission has a cliff edge drop off when it goes out of range.

9. Why do by batteries run down so quickly? ALDs mainly use small single cell batteries with a limited capacity. If the ALD is used only as a hearing aid, the batteries last a reasonable time, but the battery life is shortened when streaming music or phone conversations as these require extra power from the battery. Listening devices with receivers activated will also use the battery quicker

Assistive Listening Technology Working Group

Assistive Listening Technology Working Group (ALTWG): Previously known as the UK Children’s Radio Aid Working Group, and prior to that as the FM Working Group. This working group came into being in 2004 and is made up of professionals from Education, Health, Academia Charities and Manufacturers with specific interest in deaf children. They meet online twice a year. The Group’s principal aims are:

● to promote the use of radio aid systems among children and young people

● to promote the knowledge base about radio aids

● to influence the policy framework for the provision of radio aids

● to influence the quality and consistency of radio aid provision and practice

● to raise awareness of the importance of a positive acoustic environment.

Assistive Listening Technology Working Group (ALTWG) is a useful website - the home of the Quality Standards and the Good Practice Guide for radio aids.

Using a Test box

Stuart Whyte has authored detailed content about test box measures in Audiology Refreshers Section 6.6. “There are UK quality standards and practical guidance on electroacoustic measures for HAs, BCHDs, and auditory implant sound processors – most commonly CIs.

‘Quality Standards for the use of personal FM systems’ by the UK Children’s FM Working Group was published in July 2008 by the NDCS. This was updated in February 2017 as ‘Quality Standards for the use of personal radio aids: Promoting easier listening for deaf children’. The multi-agency group is now known as the UK Assistive Listening Technology Working Group (ALTWG).

The latest version of the guidance on QS8 Electroacoustic checks with auditory implants was published in March 2024

Of particular relevance is Section 5 of the Quality Standards on the Management and use of personal radio aids, which includes QS7 and QS8.

QS7: Subjective checks of radio aids must take place regularly.

Perform listening checks of the radio aid system daily, with and without the hearing instrument, using appropriate devices such as a stetoclip for hearing aids, monitor earphones for cochlear implants, listeners for bone conduction hearing implants, or a dedicated headphone set for the radio system.

QS8: Electroacoustic checks must be performed regularly and whenever a part of the system is changed.

Complete regular (test box) checks in order to compare the frequency response curves with baseline settings provided at the time of set-up.

A good practice minimum is every half term – this may need to be more often for young children and will depend on the user.”

A test box or hearing aid analyser is a means of analysing the output and performance of the hearing device, both with and without the radio aid. This is done by putting the hearing device along with the radio aid through the test box; you can print off the graph as a visual record. It is therefore a means of seeing the effect of the additional device and ensuring that the performance of the hearing device is not altered and that the child gets the maximum benefit from using the two together. The test box will give you the ability to print off a visual record of what the two systems are doing together.

The performance of radio aids and hearing aids can be measured and recorded over time. This is in accordance with MCHAS protocols.

“There are three common test boxes in use today in the UK (others are also available): Frye FONIX FP35, Affinity systems, and Aurical Hearing Instrument Test (HIT).

The Affinity and Aurical systems meet modern requirements for testing hearing devices (BSI 2021; 2022) and have the ISTS (International Speech Test Signal). The FONIX FP35 Analyzer needs to have the latest software to be able to select ‘Aid Groups’ as ADAPTIVE and to select the test signal DIG SPCH (digital speech). DIG SPCH is an interrupted composite signal and is not equivalent to ISTS. In addition, measurement tolerance is higher with the FP35 (see tolerance section below). The latest FP35 software is also needed to test modern HA fittings with an Open Fit Coupler.

Telecoil (t-coil) responses are known to be reduced in the lower frequencies to avoid interference in this area (Putterman & Valente, 2012). Therefore, in all test boxes, induction-loop RM system curves will be reduced in the lower frequencies and the response curves are more likely to match above 1 kHz.” (Whyte. S ‘Test box measures’ Audiology Refreshers Section 6.6)

The Ewing Foundation have produced some videos demonstrating the use of the FP35 test box.

It is important that the family, Qualified Teacher of Deaf Children and Young People, and the Cochlear/Auditory Implant Centre all work together on this at the point the CYP is ready. The audiologists at the Implant Centre will need to enable the speech processor to work with an assistive listening device and make adjustments to the internal settings through the manufacturer’s software.

Cochlear implants

The fitting a radio aid with a cochlear implant user needs careful timing and planning. It may seem unusual that an older child who has previously been using an assistive listening device, post CI surgery may need to wait before resuming the use of an assistive listening device. This is because in the first six months post-implant, the CYP will have many tuning appointments at the Implant Centre. If the CYP is unhappy with their listening experience after a tuning appointment it would be difficult to know if was due to changes to the mapping of the speech processor(s) or the addition of a radio aid, therefore a stable map is needed. There may be the occasional exception where a CYP can report accurately on their listening experience.

Bone conduction hearing aids

The principles of setting up bone conduction aids and BCHDs with an assistive listening device are exactly the same as with a hearing aid. However, you do need to have the correct adaptor to connect it in the test box.

The NDCS booklet How radio aids can help - A guide for families has a section on connecting radio aids to bone conduction aids (page 16).

Assessing the benefits of the assistive listening devices

The purpose of an assistive listening device is to make speech/sound accessible in difficult listening environments for hearing aids and CIs, by reducing the effect of distance and background noise. The assistive listening is set up and balanced before being subjectively assessed by the wearer. Objective evaluation using speech discrimination tests assesses the benefit the wearer gains as well as their functional use of their listening package.

Is it worth it? Measuring benefit in noise by Joyce Sewell Rutter and Richard Vaughan is an outline of measuring the benefit of using radio aids in noise.

The Quality Standards for the use of personal radio aids recommends in QS4 that the child’s listening response must be checked with the complete system in place.

These evaluations are usually done in ideal listening conditions with the typical mainstream classroom noise introduced, enabling the signal and noise to be measured.

Section 4 of the Quality Standards Good Practice Guide 2008 details the way the information that can be used, available tests and methods of administering the tests.

Soundbyte Solutions produced a SIN test kit called the Parrot Plus.

Speech In Noise testing is currently being reviewed by ALTWG to produce more up to date testing procedures that work with current hearing technology.

Soundfield systems and assistive listening devices

Assistive Listening Devices and remote microphone technology can be used in conjunction with a Soundfield System. The teacher uses the soundfield microphone and the transmitter is connected into the soundfield. The sound is rebroadcast from the soundfield through the transmitter to the hearing device used by the CYP.

The Quality Standards for the use of personal radio aids QS12 states that:

‘There can be a number of advantages for a deaf child when a personal radio system is combined with a soundfield system. However, such systems must be regularly and sensitively evaluated to ensure optimum use and benefit’. This can be undertaken using the test box and by speech in noise assessments.

Mary Atkin, in her study, 'Soundfield systems and radio aids: exploring the effects of rebroadcasting’ (2017) states:

‘The research concludes that Soundfield systems support the provision of a good acoustic environment within the classroom. It also finds that the process of rebroadcasting a Soundfield system through a Radio Aid system requires careful management. The research supports the need to develop guidance on the use of electro-acoustic balance and speech discrimination testing when rebroadcasting. The verification process should also include due consideration of the individual user’s preferences to support the most effective use of Assistive Listening Devices’.

The Quality Standards Good Practice Guide 2008, section 7 details how to set up and balance radio aids with soundfield systems. Although technology has advanced since this was written, the principles are the same.

Strength of evidence

There is collective research, knowledge and practice from ALTWG, BATOD, BAEA members, and others involved in deaf education, in the UK and throughout the world, showing the benefit of assistive listening technology. Advances in technology have helped to overcome the problems of listening to speech in background noise and at a distance. The evidence presented shows how this has improved the access to speech for deaf CYP.

Transferability

The collected information and advice are intended to encourage and provide evidence for the provision of the use of assistive listening devices for all deaf children and young people.

Although there are difficulties worldwide, regarding financial constraints, availability and sustainability of technology, the evidence shows that hearing devices alone are not giving full access to speech intelligibility for deaf CYP. Whatever device or system is used, the basic principles are the same.

Editor’s comments

Deafness affects children and young people's access to education all over the world. We have strived to remain unbiased against any one make or type of system, and tried to provide a range of evidence from across the range of devices and manufacturers. We welcome further case studies, using any system and device. Please send these to exec@batod.org.uk. Please also include areas you would like researched.

Online Community

There are various online forums for QToDs, allied professionals and parents of deaf children, in the UK and other parts of the world. BATOD manages an email forum for professionals linked to Deaf Education. The Scottish Sensory Centre (SSC) manages a Scottish=specific email forum for professionals. The National Deaf Children's Society (NDCS) has a Facebook space for parents https://www.facebook.com/NDCS.UK/ and a National Deaf Children's Society Professionals Community Facebook space.